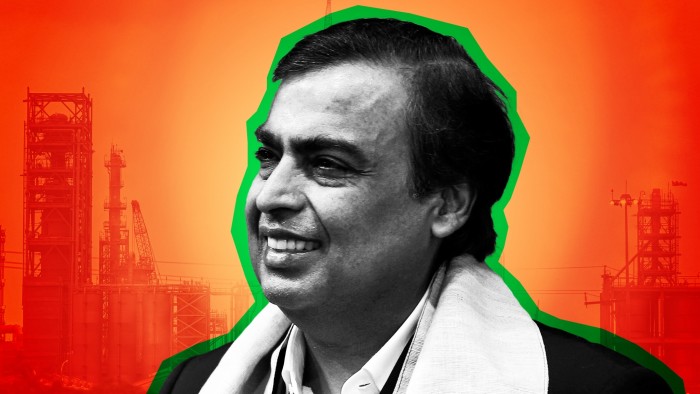

At the end of 2024, Bollywood and cricket stars, as well as India’s powerful home minister Amit Shah, descended on the industrial hub of Jamnagar in Gujarat to celebrate a milestone in the empire of Asia’s wealthiest man.

The occasion marked 25 years since Mukesh Ambani, who chairs Reliance Industries, established what would become the world’s largest oil refinery. It still generates more than half the annual revenue of a conglomerate, worth $225bn, that also straddles retail, telecoms, news, entertainment and sport.

The vast site, covering an area 10 times that of the City of London, can process 1.4mn barrels of crude per day and is of critical national importance. Nestled in a high security zone near the border with Pakistan, passengers flying into the city are ordered to shutter their windows as they come into land. Signs banning drones and photography dot the airport and surrounding industrial facilities.

Jamnagar, the birthplace of Mukesh’s mother, is also central to the family’s myth making. In March last year it hosted a multi-day function celebrating the extravagant wedding of the billionaire’s youngest child, Anant, where guests such as Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg were entertained by Rihanna.

Nita Ambani, Mukesh’s wife and head of the Reliance charitable foundation, told the audience at the 25th anniversary bash in December that Jamnagar “is not just a place, it is the soul of Reliance”.

As Mukesh himself approaches the end of his seventh decade, he is pushing Reliance towards a low-carbon and artificial intelligence-powered future that mirrors India’s ambitions. That includes plans for a major data centre and five giga factories across 5,000 acres at Jamnagar to manufacture solar panels, batteries, fuel cells and electrolysers to produce green hydrogen.

He is also plotting a generational handover to his three children, to whom the task of managing this transition will largely fall. Bruised by the bitter family dispute that followed the death of his own father, he has been at pains to choreograph a steady transfer of power.

In 2023, the tycoon said he would spend the next five years training up the new generation ahead of retirement. His children joined Reliance’s board that year, its three main units clearly demarcated. Executives at the conglomerate say they are hands-on in the businesses and decision making, working closely with senior management and being supported by renowned business leaders.

Akash and Isha, the 33-year-old twins who head the digital and retail operations, have sat on the boards of the subsidiaries for a decade. They and Anant, 30, have begun to make more frequent public appearances, though these remain heavily managed and guarded from critical scrutiny.

“They have been quite proactive,” says Harshraj Aggarwal, analyst at Yes Securities in Mumbai. The children are “quite well versed in the business”.

The twins also now deliver remarks at Reliance’s online annual meetings. Anant, who oversees its gargantuan energy business, has yet to speak in that forum, but will probably do so at the next one, according to a person close to the company.

But after years of heady growth, multiple people familiar with Reliance question — privately, for fear of angering India’s most powerful business family — whether the trio of thirtysomethings share their father’s keen business acumen or relentless drive.

“I’m not sure what to make of the Ambani kids,” says one fund manager. “They appear in public but they don’t say enough for us to make an independent assessment of their capabilities,” he adds, describing the succession as one of corporate India’s most “vexed” issues.

Mukesh has “a phenomenal missionary zeal that is difficult to match”, says one Indian executive. “It will be a tough generational transition.”

Reliance did not respond to a request for comment.

The Ambanis visibly loom over Reliance. Garlanded portraits of Dhirubhai Ambani, its venerated late founder, adorn its facilities, as do those of his son Mukesh, whose grinning image greets arrivals at Jamnagar’s airport. “It’s like North Korea,” jokes one western diplomat about Reliance’s iconography.

The vast conglomerate has been referred to as a “state within a state” given the influence it wields in India. At Antilia, the Ambani’s Tetris-like home that towers over wealthy south Mumbai, Mukesh is known to point out an area in the distance where he spent part of his childhood in a crowded tenement, or chawl, after his father returned from Yemen and began his ascent to the pinnacles of corporate power in India.

That empire building almost ground to a halt in 2002, when Dhirubhai died without leaving a will. Mukesh became embroiled in a long-running inheritance dispute with his younger brother, Anil.

After that was eventually settled, Mukesh established himself as a corporate leader to be reckoned with, overhauling the legacy textile and petrochemical business that brought the family to prominence, expanding into new sectors and comprehensively outmanoeuvring his sibling.

Rahul Malhotra, director at Bernstein, calculates that Reliance now generates more than half its annual earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation from consumer-facing businesses, compared with less than 10 per cent a decade ago. “These are the bold decisions Reliance has taken to transform their business model and now it reflects in how people think about the business,” he says.

Over the past decade, Mukesh — whose personal wealth is estimated at more than $100bn — established Jio, India’s largest mobile network after cutting down multiple operators in a fierce price war. Reliance operates the country’s largest chain of retail stores and controls one of its biggest news and entertainment networks.

Jyoti Deshpande, president of Reliance’s media division, says the overriding philosophy is scale. “If you can’t be in a business which you’re eventually able to scale, then we’d rather not be in that business,” she says.

The Ambanis are also seen as gatekeepers to multinationals entering India’s massive but capricious business landscape, which Reliance has mastered over the decades through its legendary lobbying network. After first battling both Disney and Elon Musk’s Starlink on its home turf, Reliance later brought both their Indian operations under its wing through joint ventures.

“I’ve never worked with anyone like Mukesh before,” says a banker close to Reliance, before questioning whether his offspring, brought up in opulence rather than the spartan childhood Mukesh experienced in Yemen and Mumbai, could live up to that legacy.

The children have been allotted roles that play to their interests, according to a person familiar with the family’s thinking. Akash, who graduated from the Ivy League Brown University in the US, is a “tech nerd”, the person adds.

One investor at Jio says Akash is “not power hungry” and aware that he is a “steward” who doesn’t need to be actively managerial. At a Mumbai tech conference earlier this year, Akash admitted he rarely spoke in public, thanking his family in the audience for giving him “confidence”.

On stage, Akash said he took inspiration from his father’s work ethic, noting that Mukesh clears his email inbox by 2am each night. “Now myself, Isha and Anant are trying to continue to build [Reliance’s] legacy,” he said. “No doubt they are big shoes to fill.”

Isha, a Yale graduate with an MBA from Stanford who briefly worked at McKinsey, is an “arts enthusiast” and “integrally involved” in the family’s cultural endeavours, according to a Reliance profile. These include the Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre in Mumbai, which has brought Broadway shows to India’s financial capital.

Describing herself as an “introvert” in an interview with Vogue India last year, Isha enjoys friendships with Bollywood A-listers such as Alia Bhatt. Reliance Retail formed a joint venture with Bhatt’s maternity and children’s brand Ed-a-Mamma in 2023.

However, it is Anant, also a Brown University alumnus, who has attracted the most intense speculation. He is the only one of the three to have an executive director role at Reliance, and his attendance at Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s swearing in last year and meetings with powerful state chief ministers resulted in comparisons to his grandfather, a wily operator, says a consultant who has worked with Reliance.

Reliance publicly says Anant is “passionate” about animal welfare. People close to the family say he spends much of his time at Jamnagar and is devoted to Vantara, a nearby wildlife orphanage that hosts more than 150,000 animals, and which is not open to the public.

During a February talk at Harvard University, his mother Nita described Anant as “very, very religious and deeply rooted in spirituality”. Ahead of his 30th birthday in April, Anant set off on a 170-kilometre pilgrimage march from Jamnagar to the holy city of Dwarka.

The company described the trek as a “strenuous journey” given he suffers from Cushing’s syndrome, a rare hormonal disorder that often causes obesity, as well as asthma and lung disease.

On route, Anant paused to halt a truck full of chickens, purchasing them for the Vantara refuge and personally carrying a hen away into the night. “It does not bode well for the future of the group when people see one of the next heads walking around holding a chicken,” says an analyst with deep knowledge of Reliance and its senior leadership.

One person close to the conglomerate emphasises Reliance was focused on training up experienced corporate hands to make sure the conglomerate survives “beyond” multiple generations of the Ambani family. Another says it is “too early” to judge the children’s potential ability.

“They are insulated, they are protected,” Kavil Ramachandran, professor and family business expert at the Indian Business School, says about the children. “They are the face, their operational responsibilities are pushed down to non-family professionals.”

As India’s most valuable company navigates that transition, Mukesh has focused on planning Reliance’s global expansion.

It remains a relative minnow overseas. A handful of trophy assets — including toy retailer Hamleys and the historic Stoke Park estate in the UK and New York’s Mandarin Oriental hotel — pale in comparison with the foreign ports network run by India’s second-richest man, Gautam Adani, and African telecoms network operated by Sunil Mittal’s Bharti Airtel.

But last year, Reliance’s chair outlined a goal to more than double the group’s size by the end of the decade and expand its reach abroad. Mukesh and Nita attended Donald Trump’s inauguration, posing for photos with the US president, who the Indian tycoon also met last month in Qatar. A Reliance real estate subsidiary paid a $10mn “development fee” to a Trump business vehicle for a licence agreement, according to the president’s annual financial disclosures.

Both privately and at public events, Mukesh delivers well-worn lectures on India’s upward march and Reliance’s role as a national champion. For now, many of these domestic and international ambitions remain undefined, and are likely to fall to the next generation to implement.

Reliance’s patriarch is aware of the challenges as its businesses become more diversified, says another executive close to the conglomerate. The billionaire does not see how the family “can continue to operate everything”, the executive adds. “That’s the journey they’re going through and it’s not going to be easy.”

Some of its businesses have come under pressure. Its retail arm has shed tens of thousands of staff and shuttered about 2,100 underperforming stores, though its profits in the latest quarter have shown a recovery. Indian quick-commerce and delivery service Dunzo, which Reliance backed, collapsed.

A senior banker said Reliance now faces greater resistance and its rivals “know how to fight back . . . it’s no longer easy to just enter a market and win”.

Long-term investors looking for an exit were also disappointed when Mukesh failed to signpost a clear timeline for the long-awaited public listings of Jio and Reliance Retail during his highly anticipated AGM speech last August.

Bankers have yet to be instructed, though a float of the telecoms and digital business could still happen this year, according to people familiar with the matter. One investor says “[the family] are as ready as they can be” for Jio’s IPO and are waiting for the right market conditions.

A deeper question hangs over Reliance’s plans to reposition itself as a leader in clean energy. While rivals have invested heavily in solar and wind power, Reliance has “been ridiculously slow”, says the analyst with close knowledge of the company.

“When it came to the telecom space, they really went in there with full force . . . and pushed everyone out,” says Lakshmanan R, head of south and south-east Asia corporates at Fitch Group’s CreditSights. “Comparatively, we have not seen Reliance being a very huge force when it came to renewables, even though that was the initial expectation.”

Reliance has pledged to become “net carbon zero” by 2035 — ahead of the government’s own 2070 goal — in what Mukesh has called the conglomerate’s “seva”, or selfless service. The family are transforming Jamnagar’s petrochemical complex into a $10bn green energy centre at the heart of a critical transition for India.

Yet the facility remains the world’s largest carbon-emitting refinery, according to Climate Trace. During a recent visit by the Financial Times, Reliance’s fossil fuel might was evident as petroleum tankers trundled up and down a highway leading to the complex’s maze of pipelines, cooling towers and distillation units.

Executives have urged patience. During an April presentation, Reliance’s chief financial officer, Srikanth Venkatachari, acknowledged it would take at least two years to see “anything meaningful” in solar generation as it rapidly builds out manufacturing capabilities.

“We are the only company in India that is doing every facet of the renewable energy space . . . in two years the jigsaw will fall in place,” says another Reliance executive.

Analysts say the conglomerate’s approach is familiar. “Reliance is typically not the first player to start something,” says Bernstein’s Malhotra. “But when it comes to accelerating, we have seen them do a fairly decent job of catching up with competitors which are ahead — they have the balance sheet to do it.”

Back in Jamnagar, one company owner who leads a local business group, says that while he invests in Indian stocks, he has shied away from buying shares in the conglomerate on his doorstep. “I don’t think it is the time to invest in Reliance because it needs consolidation,” he says. “They are stretching themselves too thin.”

As for the succession, he recalls the Ambanis’ now mythologised tales of their hardscrabble early years. Dhirubhai once worked at a petrol station in Yemen, and Mukesh, who was born in Aden, once said his earliest memory was living with eight people in a single room.

The businessman then quotes a local adage about the first generation being the hustlers while “the second generation enjoys the luxuries”. According to that Gujarati saying, the third generation — by implication, the twins and Anant — “will burn everything down”.