This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered three times a week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

Shareholders in US renewable energy companies are licking yet another wound. Yesterday the House passed a bill gutting tax credits for the sector which, as I wrote last week, looks seriously unhelpful to the US in its economic contest with China.

The Trump administration has also been moving against rules forcing companies to disclose their greenhouse gas emissions. But that doesn’t mean those emissions can be kept secret . . .

EMISSIONS REPORTING

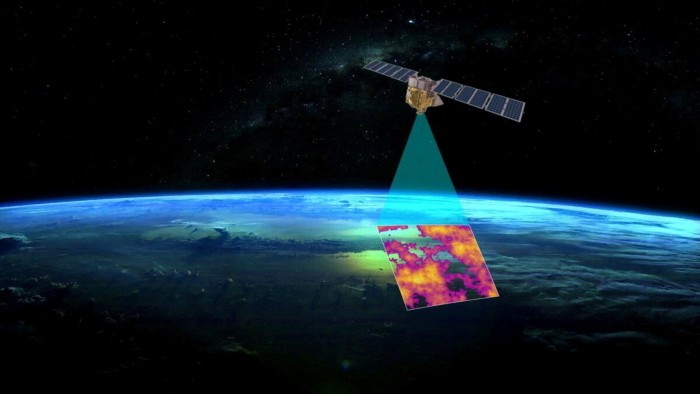

How satellites could improve emissions reporting

There’s been an explosion in the amount of environmental data reported by companies in recent years. But is it accurate?

A growing number of academic studies have given serious grounds for doubt on that front. Using information harvested by satellite systems, they’ve shown that methane emissions from the oil and gas sector are far higher than the levels reported by companies and governments.

And erroneous emissions data in the primary energy sector will inevitably ripple across the rest of the economy. If oil and gas producers under-report their operational emissions, then their customers in the utility or petrochemical sectors will understate the emissions linked to their inputs — and so, in turn, will their customers.

The latest troubling finding has come from academics at King’s College London — along with a policy prescription. It’s high time, they argue, that governments started using satellite data to hold companies accountable for pollution.

“All this sustainable financial regulation, decarbonisation policy, scenario modelling — all of it is based on a concept of greenhouse gas emissions, which, in my opinion, is fundamentally unstable,” the study’s lead author Marc Lepere told me.

The paper — which has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal — used data from Climate Trace, an open-access initiative that takes inputs from more than 300 satellites and thousands of sensors to provide estimates of greenhouse gas emissions from individual sites.

The authors calculated total detected emissions for 279 companies, and compared those figures with the ones that had been reported in their public disclosures. In theory, companies should have reported higher numbers, because the systems used by Climate Trace may not have captured all of their emissions.

In fact, the researchers found that 75 of the companies were significantly under-reporting their emissions — stating figures that were on average just a third of the level shown in the Climate Trace data. The under-reporting was particularly strong among mid-sized companies in the US oil and gas sector.

This corporate-level analysis follows a string of similar findings — notably this Stanford study which found methane emissions from US oil and gas facilities were three times the level estimated by the government.

There is good reason for the growing attention being given to methane. Over a 20-year timeframe, its warming effect is 80 times that of carbon dioxide. Industrial methane emissions come largely through eminently avoidable leaks and venting. As potent, practicable climate interventions go, cracking down on methane is hard to beat.

Lepere and his co-authors argue that governments must start using this satellite data to force more accurate reporting of carbon emissions. They suggest that authorities use this data to provide “default” calculations of each company’s emissions. Companies would then have the opportunity to appeal for a revision of this figure, if they could prove that the actual emissions were lower than suggested by the satellite data.

While today’s technology can detect levels of methane in the atmosphere, it’s unable to do so for carbon dioxide with any useful level of accuracy. Climate Trace and other initiatives have, however, started providing estimates of CO2 emissions from individual sites by tracking other indicators, such as the levels of heat at industrial plants.

While governments should start with methane, Lepere argues, they could take advantage of these technological advances to push for more accurate reporting of industrial carbon dioxide emissions too. As his team showed in a 2023 study, current methods of CO₂ reporting give companies extensive flexibility on how they estimate their emissions, creating risks of systematic under-reporting.

The new paper may be of interest in Brussels, where EU officials are working to develop a more efficient framework for corporate emissions disclosures. Perhaps less so to Donald Trump’s US administration, which is moving to strike down the extensive disclosure requirements that Joe Biden’s government imposed on the oil and gas sector around methane emissions.

This means financial investors may have a key role to play in pushing for more accurate reporting, said Mackenzie Huffman, head of strategy at Carbon Mapper, another non-profit group focused on satellite-sourced emissions data. “People are still getting used to this type of data, even though it’s been around for different uses for a long, long time,” she said. “But . . . investors are starting to actually ask the question: ‘Why is what is being reported here not matching up with your reports?’”

Smart reads

No place to hide A former McKinsey partner has been jailed for deleting emails on the consultancy’s work for opioid producer Purdue Pharma.

New direction Can Big Oil turn the US into a lithium giant?

Down but not out Europe’s solar manufacturing sector might still be in with a chance.

Recommended newsletters for you

Full Disclosure — Keeping you up to date with the biggest international legal news, from the courts to law enforcement and the business of law. Sign up here

Energy Source — Essential energy news, analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here