Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A shortage of raw materials for chipmaking is just one of the inevitable consequences of US restrictions on tech exports to China. The escalating trade row between the two superpowers — via a whole panoply of export controls, blacklisted entities and tariffs — carries ship loads of collateral damage.

Tit-for-tat restrictions are the most obvious. Beijing’s curbs on shipments of germanium and gallium, used in military communications kit as well as making semiconductors, mean western manufacturers are paying more, or going without.

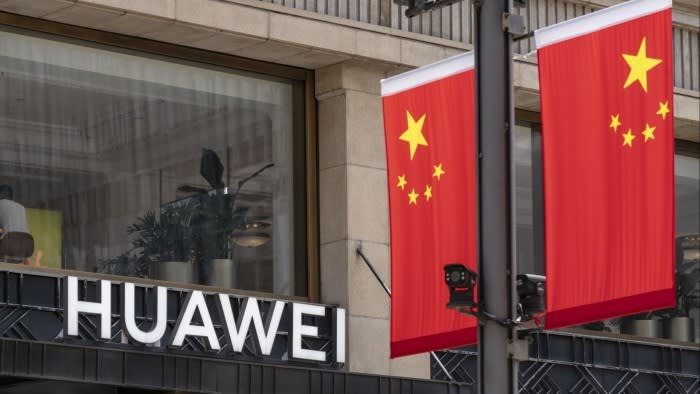

Next, withholding tech puts more impetus on the targeted country to develop its own. Huawei, the Chinese telecoms group that has long been in Washington’s crosshairs, worked with domestic chipmaker SMIC to produce its system-on-a-chip Kirin 9000S. It caught US officials unaware when various testing teams showed its performance ranked alongside one-or-two-year-old chips produced by Qualcomm.

It should not have. Beijing’s Made in China 2025 industrial policy came out nearly a decade ago and laid much of the groundwork by corralling vast troves of state funds and computer engineering talent. Take universities. Innovations from Tsinghua University alone include a particle accelerator whose electronic beam will ultimately enable it to produce two-nanometer chips in high volume.

The flipside is the dent to multinationals left with limited access to the second-biggest economy. Export controls slice 8.6 per cent off revenues and cost the average impacted American supplier $857mn in lost market capitalisation, a report from the Reserve Bank of New York estimates. Across the board that tallies up to $130bn.

Lost China business, the authors found, is not replaced by so-called friend-shoring or other new customers. Multinational corporations bear a further brunt from the US and China pursuing dual-track technologies: a petering out of global standards.

Of course all this assumes export controls are impervious. But students, and others, are proving just as adept at smuggling in AI chips. Enforcement would appear to be patchy.

Companies can also sell less advanced chips not bound by the restrictions. Nvidia is reckoned by analysts to make £12bn in China from such sales this year. The same strategy enabled ASML to garner just shy of half its total net sales from China in the last quarter — less than 18 months after the Dutch government partially revoked a licence for the shipment of two lithography systems.

Numbers from US equipment managers imply a similar story, at least for now. China accounted for 39 per cent of sales at Lam Research in the latest quarter, up from 26 per cent a year ago; at Applied Material the share rose from 27 per cent to 32 per cent. Investors will hope these trajectories continue.

louise.lucas@ft.com