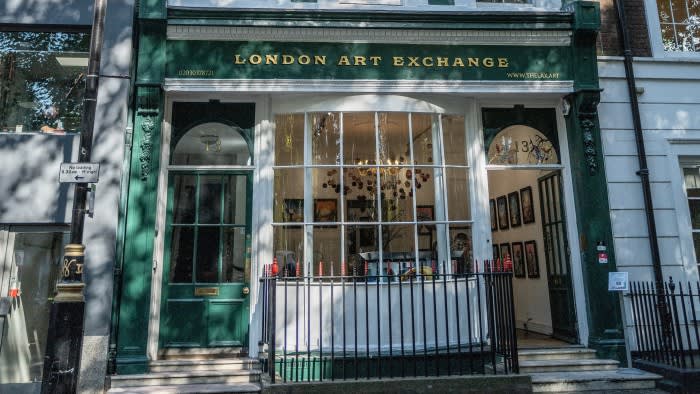

Located in the heart of London’s West End, the three-storey Georgian townhouse at No 13 Soho Square has seen no shortage of changes over its 266-year history. Yet few, if any, match the scale of the ground-to-roof refit planned by its current owner.

Pelham Olive, a 68-year-old serial entrepreneur, bought the 6,500 sq ft, Grade II-listed building in 2015. Almost immediately, he put his mind to converting it from its use at the time as a media post-production studio into a private family residence.

To add to the challenge, he wanted the resulting refurbishment to meet the “outstanding” category of the BREEAM standard, a leading certification for green buildings. “It’s hugely difficult because not only is the property right in the middle of town, but it’s also highly protected in conservation terms,” he says. “But I want it to be an exemplar, to show that it can be done.”

Breaking with the conventional mould, Olive is one of a small but growing number of luxury property owners looking to put environmental considerations at the heart of their dream home.

Motivations differ. Some, such as climate-conscious Olive, see lowering the 37 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions linked to buildings and construction as an essential part of “saving the world”. Hence, the inclusion in his refurbishment plans — which, he admits, are “about two inches thick” — of everything from ground source heat pumps and “passive” ventilation to a roof garden stocked with carbon-sequestering planters.

Others take a slightly harder-headed view. Alastair Alderton, for example, recently commissioned a family home for himself in the leafy London suburb of Dulwich. Alderton, who is the chief executive of a boutique investment advisory firm, ran the numbers and decided that a super low-energy design was a “no-brainer”.

It worked. Not only does the heating and cooling of his gold standard “passivhouse” home more or less pay for itself, but the clean power generated by a rack of solar panels (hidden discreetly in the dip of his split pitch roof) also significantly reduces his electricity bill.

Should he ever come to sell, meanwhile, he hopes the property’s eco-credentials will garner a healthy premium. The comparators certainly look promising. He points to similar-sized houses in a dedicated conservation area nearby, one of which was recently advertised at £10mn. “One would imagine that the environmental features will push the prices of those houses up further,” he says.

Caryn Black, co-founder of Pennsylvania-based real estate company B&B Luxury Properties, which specialises in eco-friendly homes, agrees. Nor is it just ecology and economics persuading wealthy homebuyers to pay more, she says. Wellbeing, too, is fast becoming a priority concern. Sure, people get a nice feeling from knowing their house is insulated with hemp; but the knowledge that some chemical-laden foam concoction isn’t lurking behind their walls makes them much happier.

Pioneers of the green building movement may not have promoted the wellbeing benefits of their designs historically, but the fact that eco-homes are typically cleaner, healthier and more wholesome remains no less valid for their silence.

Luxury realtors are now making up for lost time. On Black’s books at present, for example, is a $4mn “near-zero” carbon footprint house in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Rarely is it the gourmet SieMatic kitchen or the Jack & Jill bathroom suites with tray ceilings that prospective buyers comment on, she says. Instead, it’s the purity of the air and the parkland views from the top-floor glass tower.

“People are really into the fact that the house doesn’t use any oil and the paint is all toxic-free and stuff like that,” she notes. “When they walk in . . . they immediately comment on how light it is and how clean the air feels.”

It’s a trend to which Claire Reynolds, managing partner at Sotheby’s International Realty in the UK, can also attest. Younger wealthy buyers (under 45) are particularly sensitive to the nexus between people, planet and their own property.

That said, opportunities to land the perfect eco-house remain in relatively short supply, she concedes. Either it requires a client with a very clear idea of what they want — and a willingness to pay for it — or a developer with the vision to step outside the norm.

The list of the latter is growing slowly. MariSol Malibu is illustrative of their ilk — namely, eco-focused and unapologetically upmarket. The California-based developer started in 2014 with plans for 17 “100 per cent electric”, “100 per cent renewable”, and “100 per cent clean” luxury homes on an exclusive stretch of Malibu coastline.

Averaging just one property a year, progress is slow, admits Scott Morris, the company’s director of carbon reduction and sequestration. Yet just having an employee with his job title indicates the attention given to every detail, from the recycled content of the aluminium roof (99 per cent) to the level of operating carbon (zero tonnes).

Morris reserves his main enthusiasm for MariSol’s use of low-carbon cement. In place of the standard Portland variety, which is alone responsible for up to 8 per cent of all anthropogenic emissions, the company uses a non-clinker alternative based on pozzolan — a natural siliceous material that hardens when mixed with calcium hydroxide.

Not only is the cost of natural pozzolan “considerably cheaper”, he says, but its performance is better: more impermeable, more resistant to corrosion and longer lasting. So why don’t more builders use it? Inertia, he says: “Contractors just have a risk aversion to novel materials.”

Such attitudes aren’t fixed in stone, however. The sale of MariSol’s latest property garnered “extraordinary” publicity, Morris points out. While most of the headlines focused on the home’s nine bathrooms and $28mn price, its eco innovations also caught the eye of the wider building community.

As he says: “I’ve heard examples of contractors calling up concrete companies and saying, ‘How do I do this?’. I was talking to a guy in the industry and he said, ‘You know, in 20-plus years, no one had ever called me to ask about low-carbon concrete.’”

Both culturally and commercially, the eco-building sector is traditionally associated with affordable housing and public-sector projects. However while that remains largely true, many also acknowledge the potential of the luxury market to put sustainability squarely on the map.

For example, Jon Bootland, chief executive of the Passivhaus Trust, a leading proponent of greener construction, notes the “buzz” created when a certified eco-home was named a finalist in the UK’s prestigious RIBA Home of the Year awards in 2021.

Indicative of changing times, the trust recently introduced a new category of membership explicitly for individual homeowners. While Bootland remains concerned that sustainability is not seen as “only for the super-rich”, he is more than happy if wealthy proponents want to “evangelise” for the cause.

Alexandra Nicolau, owner of Kerridwen Green, a Mallorca-based real estate company specialising in green construction, goes even further. By pushing ahead with the newest tech and designs, she argues, wealthy homeowners can help bring down the high costs often associated with sustainability.

“The only way of making sustainable real estate more affordable is to create demand,” she reasons. “And the only way of creating demand is to get those who can afford it to open their pockets and invest in it.”

It is not an outlandish proposition. Government support, after all, has helped make solar panels and ground source heat pumps more accessible. Could high-end homeowners do the same for cutting-edge smart home technologies, say, or sophisticated energy management systems?

That remains to be seen. Innovative as the luxury housing sector may be, its total investment pool is a fraction of that represented by the commercial property market. As a driver of technological breakthroughs, it may be a better bet to look to a multi-billion-dollar gigafactory or the headquarters of a Fortune 500 company.

That said, the lessons learnt on individual residential projects can be invaluable. The luxury market has the “financial flexibility” to experiment, observes Jessica Grove-Smith, joint managing director at the Germany-based Passive House Institute. Novelty brings knowledge, she argues: “Everybody involved in a project learns something, and then takes those lessons to the next project.”

That is certainly the thinking of US developer Blue Heron, a high-profile proponent of eco-innovation and vendor of one of the most expensive residential properties in Las Vegas’s history. The building in question, Vegas Modern 001 or VM001, which fetched $25mn in 2021 (and has recently been relisted), features an “intuitive” energy management system that syncs with its owners’ circadian rhythms using touch-operated panels or a smartphone app.

With 300 or so solar panels on its roof, the 15,000 sq ft villa also doubles up as a mini power station: a state of the art $200,000 battery storage unit controlled by automation software sells power to the grid at the highest price. There is also a storm function, which reduces power usage should the grid go down.

Today, Blue Heron is about to break ground on a successor project, VM002. Tyler Jones, Blue Heron’s founder and chief executive, sees it as an opportunity to put into practice fresh insights gleaned within his company and the building industry at large. “At the time, VM001 represented all our accumulated knowledge — in design, in sustainability, in technology, in everything,” he says. “VM002 will be the updated version, including everything we’ve learnt since then and the most forward-thinking ideas in all those different categories.”

Back at No 13 Soho Square, in London, entrepreneur Olive has called in the estate agents. With his plans now certified, he is keen to see someone else undertake the completion of the project. At £7.65mn for the building, plus an additional £3mn for the renovation, it is no small undertaking. Does he have an ideal buyer in mind? He does, he says: “Somebody who cares.”

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment