Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

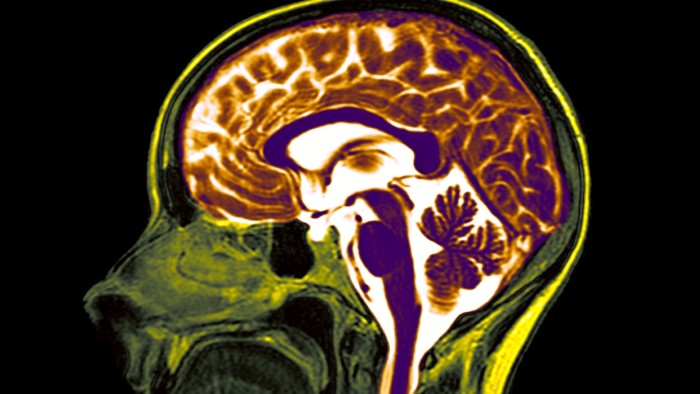

The first sign something was wrong was when I noticed the radiologists pointing at the screen. I was lying in an MRI tube having genuinely enjoyed half an hour of pounding industrial techno music generated by the imaging machine. A needle full of ink was unexpectedly, and painfully, inserted into my right arm. Then I spied the imaging staff pointing at something they didn’t like the look of.

I’d had the MRI to rule out anything serious after an unusually intense migraine the night before. My GP called me later that day to tell me that an arachnoid cyst had been found on my left cerebellopontine angle. It wasn’t “the worst”, he said, but it wasn’t great either. I recalled the old Woody Allen joke about the most beautiful words in the English language being “it’s benign”.

My family was on holiday at the time, so I was sitting alone in Sydney, a city where I’d only recently moved, with news I wasn’t sure I fully understood.

The arachnoid membrane takes its name from its spider weblike texture. It is one of three layers that protects the brain and spinal cord. Mine had been damaged at some point, creating a cyst that was filled with spinal fluid. It was putting immense pressure on my brainstem.

The symptoms I’d been experiencing began to make sense. Blurred vision in my left eye. A tendency to drop my phone when carrying it in my left hand. A decrease in co-ordination, which perhaps explained my declining batting average in recent years. These could soon send me sprawling in the street, I was told.

Arachnoid cysts are most often identified in children with developmental problems, and they are usually found at the front of the brain. It is rarer to discover one at the rear of the skull in a middle-aged man. No one could explain why I had the cyst. It may even have been there since birth. I visited two neurosurgeons after it was discovered in late 2022 and both recommended leaving it where it was as, at my age, the risks of operating in that region of the brain outweighed the benefits. But by February the following year a new scan showed that it had grown significantly.

I could see for myself from the MRI images delivered to an app on my phone that the white orb was now bigger than before, and it was muscling my brainstem off its centre. By then, I had started suffering vertigo-like symptoms and my balance was faltering. A friend I hadn’t seen for 20 years wondered whether I could hold my drink like I used to on seeing me stagger after only a couple of beers.

A few months before, my neurosurgeon, a man of few words, told me that the risks of operating included blindness, deafness, infection and a stroke being triggered. Now I was being given more precise odds of such eventualities. “Anything can happen,” he warned.

Those facing brain surgery often don’t know where to turn or how to cope. It can put incredible strain on a family or relationship, and the fear can become paralysing. For my part, I felt strangely sanguine as my brother had endured a much more serious brain operation a year earlier, which put things in perspective. The most intense stress I felt was having to tell family, friends and a small group of colleagues.

“It’s not a tumour,” I would joke, imitating Arnold Schwarzenegger in Kindergarten Cop, to ease the panic in their eyes when I told them I was getting brain surgery. Yet I found myself penning tear-stained letters to my children, just in case. I feared a radical change to my personality. Who would emerge on the other side?

Such thoughts plagued me as I entered the hospital that March. When I dropped my kids at school that morning, they said they hoped the popping of the lychee — the nickname we’d given the orb inside my head — went well. We joked that if I was killed by the lychee I might appear on “Stupid Deaths”, the segment on the television series Horrible Histories where a jolly Grim Reaper interviews a historical figure about their humiliating demise.

After several hours of surgery I woke up in intensive care. A nurse named Princess insisted she needed to wash me down. That confused me until she sponged swaths of dark dried blood from my neck. I remembered I’d had someone poking around inside my head only an hour or two before. I felt the lengthy scar running down my hairline behind my left ear. The eviction had been successful.

My recovery was swift and the pain was manageable. The brain itself does not feel pain. I was home four days later, and I experienced a short period of mania. I watched the Todd Solondz movie Dark Horse, which had me raving like a sports commentator. I sat on the hill at Leichhardt Oval to take my daughter to her first rugby league game and felt on top of the world.

Then I quickly regressed into exhaustion as my body settled into a more normal pattern of recovery. Something had changed, however. Popping the lychee had made me less quick to anger.

My energy levels increased as the weeks went on. I started to do the Bay Run in Sydney, listening to playlists of brain-related songs I’d been gathering. I felt more determined, less encumbered and more balanced, literally — trends that have endured. It had been a crash course in brain surgery, as the Metallica song has it, but ultimately I was better for it.

Eighteen months later I was back in the MRI tube to check that the spinal fluid sluice in my skull was working. It was. With a wry smile, my neurosurgeon told me that he never wanted to see me again.

Nic Fildes is the FT’s Australia and Pacific correspondent

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram