Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Twenty-five years ago, Intel made history by becoming one of the first two tech companies to be included in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Now, Nvidia — also a chip company — has replaced Intel in the blue-chip index following a seven-fold gain in its share price over the past two years. This is just the beginning of the shake-up facing the chip sector.

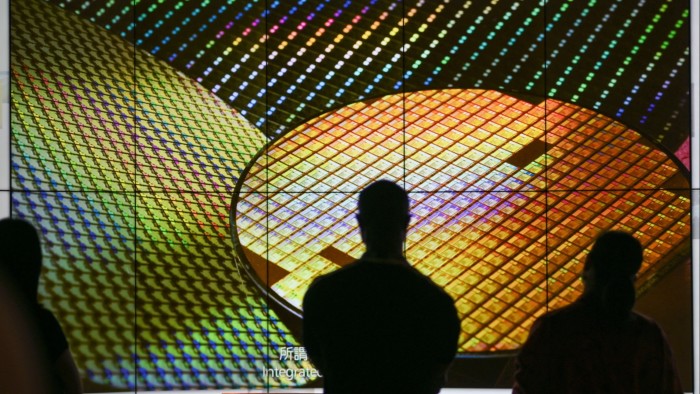

Demand for artificial intelligence chips that power generative AI technologies remains strong, with high-end AI chips still in short supply. Meanwhile, there are only a handful of chipmakers operating in this lucrative market — which would seem to guarantee earnings growth and share price gains for the sector.

Yet investing in chip stocks has been an extraordinarily risky bet this year. Shares of Intel are down nearly 50 per cent while Nvidia has tripled, now the best performing stock in the benchmark. What is behind this extreme divergence in fortunes between chip stocks?

The industry faces three big issues. The first is that most chipmakers are currently lagging behind in the field of designing and manufacturing high-performance AI chips. Nvidia’s advanced designs mean chipmakers are now being held to higher standards than when most global chip demand came from smartphones and carmakers. Increasingly stringent quality standards means long lead times for the few chipmakers that have the skills and cash to make advanced chips.

Second, two of the world’s biggest chipmakers able to make high-end AI chips are currently struggling to recover from previous mis-steps. For Intel, it took just one delay in making changes to its factories that would have made its chips faster in 2015, for its global chipmaking lead to start unravelling.

The delay, compounded by under-investment, meant it took Taiwanese rival TSMC just two years to close the technology gap with Intel, when it started making 10-nanometre chips in 2017. The gap has widened further since and Intel has ceded its manufacturing edge to TSMC.

Intel has a negligible presence in the contract chip manufacturing business — an especially lucrative segment as Nvidia outsources the manufacturing of its physical chips — compared with TSMC’s 62 per cent market share. The same goes for Samsung, which has fallen behind SK Hynix in making high-bandwidth memory chips — a critical part of all Nvidia AI chips. SK is expected to account for a market share of over 52 per cent this year, according to TrendForce data, overtaking Samsung.

Third, as with real estate and cars, the premium segment of chips has been dramatically outperforming the rest of the market. The profitability gap between high-end chips and general-purpose memory chips, or legacy chips which are used in traditional electronics, has widened in recent years. That is in part because of slowing demand for devices such as smartphones and PCs. But the biggest factor is that the average selling price of high-performance chips for AI use is about five times higher than that of conventional memory chips.

That has accelerated a winner-takes-all trend in the chip sector. It is no coincidence that the two best performing chipmakers in the world this year are Nvidia’s two main suppliers: TSMC posted a record net profit for the latest quarter and lifted its revenue forecast for the year, while SK Hynix reported a record operating profit for its latest quarter. Both reported operating margins of more than 40 per cent in the third quarter, more than double that of its peers. Shares of TSMC are up 80 per cent this year, and SK a third.

That means the stakes of falling behind are now higher than ever. Samsung missed profit estimates for its chip business in the latest quarter, while Intel posted its biggest ever quarterly loss of $16.6bn, despite making its own AI chip to take on Nvidia’s. Intel also scrapped its Gaudi AI chip sales forecast of $500mn for 2024. To put that in context, sales at Nvidia’s data centre business, which makes AI chips, hit $26.3bn in the quarter to July.

A growing glut of traditional memory chips is expected to further pressure prices and margins of these products in the coming quarters. High-margin AI chips are increasingly becoming the only way to offset that weakness. In an AI world led by Nvidia, the message to global chipmakers is clear: if you can’t beat it, join its supply chain.

june.yoon@ft.com