The Democratic Party faced a brewing crisis on Friday as a wide range of lawmakers, party officials and activists began to actively consider what had previously been a pipe dream for pundits and worried voters: the prospect of replacing President Biden on the ticket, barely four months before Election Day.

For two years, leading Democrats limited their concerns about Mr. Biden’s performance and age to private meetings and off-the-record conversations, leery of undermining an incumbent president in a rematch against former President Donald J. Trump.

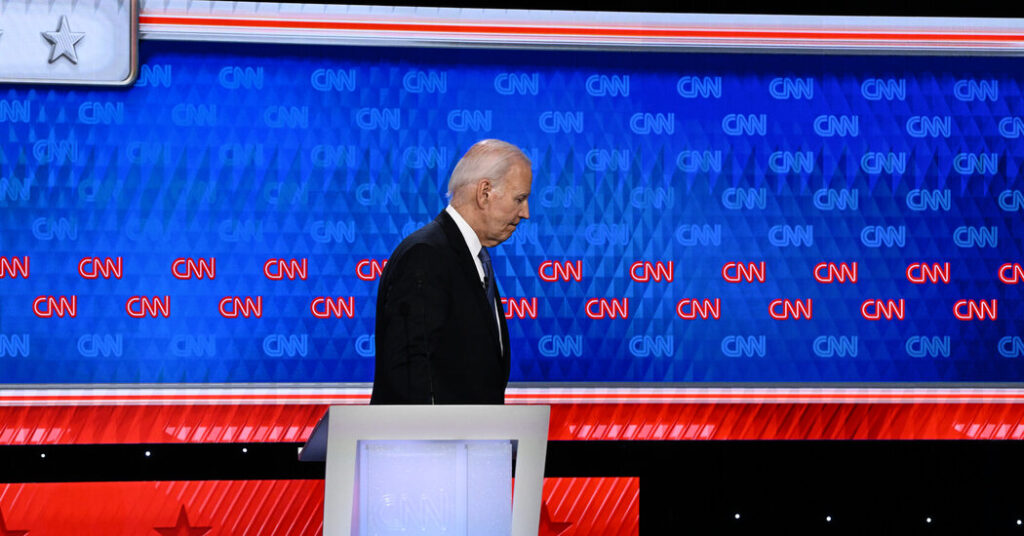

But with Mr. Biden’s debate performance on Thursday — uneven and at times incoherent, halting even on politically advantageous subjects like abortion rights — that conversation has exploded into the public domain.

“Biden did not rise to the occasion and is going to cause a serious reassessment among his party: Are they going to say, Is he just having a bad night, or is he prepared to go forward?” the Rev. Al Sharpton, a civil rights leader who has had a warm relationship with Mr. Biden for years, said in an interview hours after the debate.

Asked for his own assessment, Mr. Sharpton replied that he hoped that it had been merely a “bad night.”

“But to not be able to rise to the occasion,” he added, “is not going to be easily forgotten.”

On Capitol Hill, some Democratic lawmakers openly acknowledged that Mr. Biden’s performance was a disaster, while other leaders offered only terse signs of support and hoped that the focus would turn back to Mr. Trump’s lies.

In Atlanta, Biden aides met privately with worried donors. Their anxiety over “Trumpocalypse II,” as one adviser to a top party funder called it, had reached new heights overnight.

In message threads, Democrats vented their despair, aired their regrets about not pushing for a competitive primary contest and speculated about their options for a Biden alternative. And on “Morning Joe,” the MSNBC morning show that has been a bastion of support for the president, one of the hosts all but issued a call for him to drop out of the race.

Some Democrats were blunt in private, saying flatly that Mr. Biden should not be their nominee. But his critics acknowledged that as of Friday morning, there was no agreement — never mind formal plans — on how, or whether, to urge him to step down from the ticket.

Such an extraordinary process, many said, would carry significant political risk, hurling the party into a messy internal battle less than three months before early voting begins.

The fallout is not yet clear in public polling, and top Democratic leaders swiftly and unequivocally ruled out the idea that Mr. Biden would or should step aside. The decision is effectively his alone: He would almost certainly have to release his own delegates, freeing them up to support another nominee. So far, the president and his campaign have indicated that he does not plan to step aside.

“Absolutely not,” said Mia Ehrenberg, a campaign spokeswoman.

Mr. Biden both acknowledged his stumbles and emphasized that he planned to stay in the race during a rally on Friday in Raleigh, N.C.

“I know I’m not a young man, to state the obvious,” he said. “I don’t speak as smoothly as I used to. I don’t debate as well as I used to. But I know what I do know.”

“I know how to do this job,” he added. “I know how to get things done. I know — like millions of Americans — I know when you get knocked down, you get back up.”

One senior party strategist said the circle of Democratic leaders with any ability to persuade Mr. Biden to drop out of the race was limited to top members of Congress; former Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton; and, of course, Jill Biden, the first lady, and the rest of Mr. Biden’s family.

“Bad debate nights happen,” Mr. Obama said in a statement. “Trust me, I know. But this election is still a choice between someone who has fought for ordinary folks his entire life and someone who only cares about himself.”

Asked on Capitol Hill whether Mr. Biden should leave the race, Representative Hakeem Jeffries of New York, the top House Democrat, replied, “No.”

Representative Nancy Pelosi of California, the former House speaker, said that she did not think Mr. Biden should step aside as the party’s presidential nominee and that she did not know of anyone pushing him to do so.

Other lawmakers were unvarnished about their anxieties: “I’m still processing what happened,” said Representative Angie Craig, Democrat of Minnesota. “It was a terrible debate, we all have to acknowledge that.”

Just as revealing was what was left unsaid. Asked if Mr. Biden could do the job, Representative Ro Khanna of California, a Biden surrogate, said, “I defer to the president’s judgment on it.”

“We as a team can do it,” he said. “We have a great team of people that will help govern.”

Mr. Biden, he added, “is the person who has the delegates.”

Gov. Jared Polis of Colorado, a Democrat, said Mr. Biden had presented “a compelling vision for the country” at the debate. But asked whether he thought Mr. Biden should continue as the nominee, he did not answer directly, repeatedly changing the subject back to Mr. Trump.

“Donald Trump shouldn’t continue to be the Republican nominee after being convicted of a felony and the instability and inability to tell the truth that he’s shown time and time again,” he said.

Julián Castro, a Texas Democrat and former housing secretary who took a swipe at Mr. Biden’s memory during a Democratic primary debate in 2019, criticized party leaders who helped ensure Mr. Biden did not face a credible challenger.

“The Democratic establishment, at Biden’s urging, decided to go all in with Biden,” he said. “Once Biden made the decision to run, the Democratic side closed off all other options. And undoing that four months before the campaign is something that only that establishment is going to be able to do.”

Mr. Biden’s team spent Friday morning racing to reassure supporters. In the basement of a downtown Atlanta hotel, one floor below a coffee shop called Jittery Joe’s, top Biden campaign officials — including the campaign chairwoman, Jennifer O’Malley Dillon, and the campaign manager, Julie Chavez Rodriguez — huddled with major donors who had traveled to the debate.

Ms. O’Malley Dillon acknowledged Mr. Biden’s poor performance but tried to draw a parallel to Mr. Obama’s weak showing in the initial 2012 debate, according to multiple attendees. She was his deputy campaign manager during that race, which Mr. Obama won.

Plenty of party leaders have publicly rallied behind Mr. Biden, including several Democrats often discussed as future presidential candidate material. Governors including Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania and J.B. Pritzker of Illinois offered support, while Gavin Newsom, the governor of California, was in the debate spin room for Mr. Biden on Thursday night.

Mr. Biden has survived rough debates before, and a campaign spokesman, Kevin Munoz, wrote on social media that “11PM-12AM was the campaign’s best grass-roots fund-raising hour since launch.” The campaign added on Friday that the team had raised $14 million on debate day and the next morning.

Dmitri Mehlhorn, the political adviser to one of the party’s biggest donors, Reid Hoffman, warned his network against making rash decisions.

“Joe had a horrible night, cementing concerns about his age, his greatest electoral weakness,” Mr. Mehlhorn wrote. “Our odds of Trumpocalypse II just materially increased.”

He added: “Still, we all need to take a deep breath. Reactive or panicky moves rarely succeed.”

Senator John Fetterman, Democrat of Pennsylvania, was flying back from Israel during the debate, but said he was “distressed” to see the videos and reaction online.

“We can all agree that it was rough, but just the way everyone was so quickly to panic and pile on, my heart really went out,” he said, recalling his own halting debate performance during the 2022 campaign after a stroke. “Joe Biden didn’t have his best day. But that is not the sum total of a great president that he’s been. And how can anybody ignore what the alternative is?”

He said voters should “chill out, enjoy a beer, enjoy July 4 a little bit.”

But some Democratic National Committee members were grappling with whether the party had been right to fall in line behind Mr. Biden, though it is inconceivable that the D.N.C. — functionally the political arm of a Democratic White House — would work against an incumbent president from its own party.

“I feel responsibility as a D.N.C. member, that, some of us had reservations about Biden running for a second term early on, but very few of us actually voiced them publicly,” said Bart Dame, the Democratic national committeeman from Hawaii. “We could have at least anticipated the possibility this might be a problem. And we created structures that made it so that it’s difficult for us to respond now.”

“Shame on us,” he added.

If party officials have been reluctant to openly air concerns about Mr. Biden’s age and fitness, voters have been clear.

“Biden needs to stand down, and I did not come into this debate thinking that,” said Mac Hudson, 57, an independent voter in Tucson, Ariz. “Hopefully this will be the best possible outcome. Trump can be beat, but not by Biden. There’s still time for a new candidate.”

The moment was a painful coda for the handful of Democrats who had been publicly calling for Mr. Biden to step aside.

James Zogby, a pollster and longtime Democratic National Committee member, said that he felt “sad and distressed” watching the debate.

When he and others had called for a competitive primary, they were rebuffed by party leaders.

“Now it’s got to be — if it happens — it’s got to be dramatic and it could be fatal,” he said. “I’m upset that they have put us in this position.”

Reporting was contributed by Shane Goldmacher, Theodore Schleifer, Maya King and Reid J. Epstein.