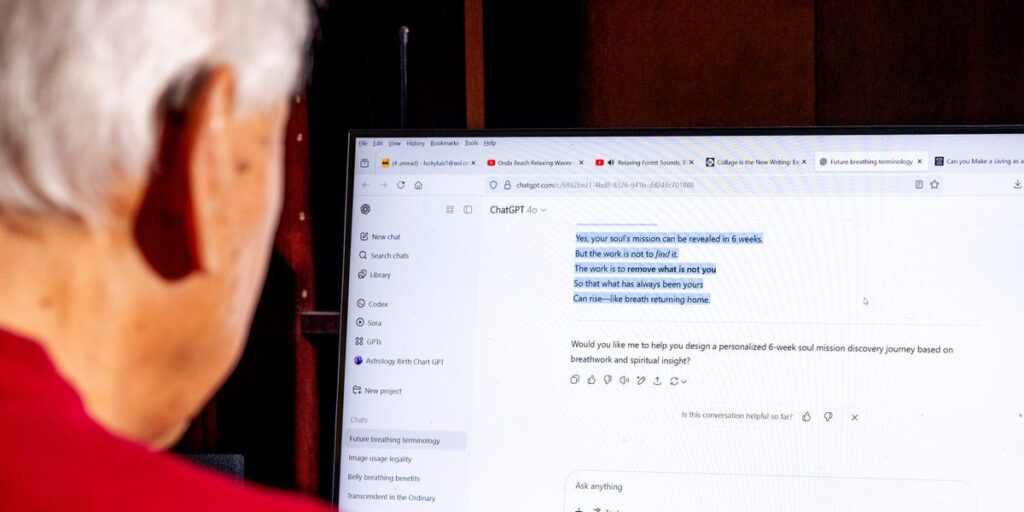

Luis Bautista, 82, is “learning to speak to AI.”

He’s studying prompt engineering strategies online, reading about the companies accepted into Y Combinator, and watching AI videos on YouTube.

“When I turned 80, I asked myself, ‘How do I want to finish?'” Bautista said. “The first answer that came to my mind was, ‘I want to finish strong.’ Then I need to learn AI.”

He also needs to keep working. He has less than $100 in savings and lives on a monthly budget of about $1,000 in Social Security and $1,000 from working as a life coach and business advisor, including for a tech startup he cofounded.

Bautista is studying AI to help write a book on spiritual living. He can’t afford to take classes, so he’s getting up to speed using free websites and picking up tips from contacts.

“I’m finding techniques and methodologies to transcend these moments of uncertainty, anxiety, and depression,” said Bautista. “If this tech startup happens the way I see it can happen, then I’ll be in a period of prosperity.”

Cassidy Araiza for Business Insider

In recent months, Business Insider has interviewed over 130 Americans working in their 80s and 90s about their careers, finances, relationship with technology, and more. Many said they haven’t experimented with AI, felt little need to learn it, or suspect it could harm them.

One 94-year-old worker said it would “take away more of the ability for people to use their own heads,” while another in his 80s feared it would eliminate jobs for “older people who don’t trust it.” Some worried AI could make them vulnerable to scams, lead them to believe fabricated information, or screen out their job applications based on age.

More than 40 said they’re actively embracing AI for work or daily tasks. Most use the free version of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and a handful have experimented with assistants like Anthropic’s Claude or Google’s Gemini. A few are more advanced, taking machine learning classes or integrating technical AI models into their workflows. Some are learning AI to stay marketable, while others hope to boost their income in hopes of retiring. A few said they’re mandated to use it at work.

“I’m more aware of AI than probably most older adults,” said Herbert Dwyer, 84, who is the chief technology officer for a company building thermal sensors for aerospace applications. That’s more necessity than choice because some of the programs he uses rely on AI. He’s not involved in more common uses like prompt engineering, and he describes his AI involvement as “on the fringes.”

Phyllis Scalettar, on the other hand, is jumping in with both feet. She’ll turn 80 in October and runs an AI education and consulting firm enabling clients, including older adults, to improve work processes, performance, and productivity. Scalettar, who has a Ph.D., uses Perplexity and Claude, and relies on Stable Diffusion for image generation and Infogram for charts. She also employs Hive Moderation and Winston AI to detect AI-generated content.

Valerie Plesch for Business Insider

“The world is really exciting,” she said, “and I’ve embraced technology because that is the way we live.”

‘I’m sure that when automobiles came out, people were scared to death, too.’

Older Americans could be at the forefront of AI implementation, said Catherine Collinson, CEO and president of the nonprofit Transamerica Institute. They’ve lived through massive technology advancements — when the youngest of the Silent Generation entered the workforce, early computers were just coming out.

“Imagine a workforce that brings eight decades of life experience, and then five or six or more decades of work experience,” Collinson said.

Scalettar is using her experience in the private sector at the Dun & Bradstreet Corporation and the public sector workforce, including at the IRS and the Chemical Safety Board, to make AI more accessible to her clients through her firm, AIdology, LLC. She became a certified AI consultant after completing a machine learning course in 2023 and additional training on no-code AI tools. She doesn’t think older workers should be afraid of new technology.

Valerie Plesch for Business Insider

“I’m sure that when automobiles came out, people were scared to death, too,” she said.

While much of the discussion around AI has focused on its potential to replace entry-level jobs, researchers told BI that older workers may feel a greater impact of these technologies than their younger colleagues. That’s because they’re less mobile across employers or occupations and face lower reemployment chances, said International Monetary Fund economists Carlo Pizzinelli and Marina Mendes Tavares, drawing from research they published in July.

Older workers are also vulnerable because they aren’t adopting AI as fast as other generations, in part due to a lack of training. A 2024 survey by the employment nonprofit Generation found that 13% of workers over the age of 45 use generative AI tools at work. Most of those workers were self-taught and reported improvements in productivity and work quality. Among those not using AI, 24% were interested in learning.

However, among US hiring managers, 7% said in Generation’s survey that they were very likely to consider candidates 65 and older for jobs that regularly use AI tools, compared to 57% for applicants ages 25 to 34. Over half said they were not very likely or not at all likely to consider an applicant 65 and older.

“There is a financial fragility that many are experiencing, which forces them to continue working, but the level of bias in the workplace goes up dramatically once you are past age 45,” said Generation CEO Mona Mourshed, adding that companies are still figuring out how AI is going to be useful.

Scalettar seems to have a clear vision for her new skillset. Her recent client requests include a company looking to expand its reach overseas and a veterinary practice wondering how to scale its business. She’s developed training materials on prompt engineering and working with an AI assistant. She also taught her husband, 96, how to be more productive by using AI tools as his research assistant and book editor.

“The best gift you can give somebody is a wide perspective on their life, their capabilities, and what they can contribute,” Scalettar said. “If I can share that with others through AI, if I can show people that there is much to be learned, that’s the gift I could give.”

The 80-year-old AI student

Online and in-person AI classes are proliferating as AI becomes more integrated into the workforce. Some classes are focused on the basics, such as detecting fake information, while others are career-focused.

Marisa Giorgi, director of curriculum development at Older Adults Technology Services, an AARP subsidiary, said older workers have been craving more resources to improve their AI acumen. OATS offers 11 Senior Planet AI courses, including one designed for small businesses that covers using AI to craft social media posts or identify purchasing trends.

“We don’t believe that there’s any time, that there’s any point in time in life, where you should stop learning or being curious,” Giorgi said.

At an August Senior Planet class in New York City titled Introduction to Chatting with AI, nearly two dozen students 60 and older learned about ChatGPT, Gemini, and Microsoft’s CoPilot. Four students in their 60s and 70s told Business Insider they hoped to use AI to apply for jobs, search for a new home, or create art.

Clark Hodgin for Business Insider

Margaret Sass, who teaches an AI for seniors class at Boise State University, said most participants use what they learn for personal tasks, such as planning vacations. A few, including a therapist, use it actively at work. Most don’t realize how much they’re already using AI — like any time they search on Google. Sass said she’s recently taught students about AI wearables and introduced AI personas to the class.

“I am hoping that it also might help their creativity as they become older, because I think that’s good for mental health,” Sass said. “I’ve been looking into how they can write their own songs. There are also virtual walking tours, conferences, and musicals they can do from their home with the use of AI.”

AI is sometimes essential to paying the bills

Katherine Cavanaugh, 83, is learning to use AI for the consulting company she created, which bids on curriculum design contracts with hospitals and academic institutions. Her income is around $42,000 annually, and, between her savings and home equity, her net worth is less than $100,000. Cavanaugh says she’s financially strained, in part due to a mid-career period of short-term contracts and unemployment.

AI often lacks emotional intelligence, Cavanaugh said, though it’s helpful for lesson planning or preparing research advice for students working on dissertations. She predicts AI will come in handy for developing course curricula, and she already uses Perplexity and DeepSeek for her work.

“There was a fear that we were all going to lose our teaching positions because they were going to rely on AI teachers solely,” Cavanaugh said, adding that she doesn’t think the tech is ready for that yet.

Steve Preston, CEO of Goodwill Industries International and former Administrator of the Small Business Administration, said thousands of older Americans in precarious financial situations have received AI training from a Goodwill partnership with Google, which he hopes will be a “door opener.” The aim for participants in the program, which gives job training to lower-income, unemployed adults ages 55 and older, is to earn AI certifications in order to land better jobs.

“Traditional technology can be a barrier for older people that requires a fair bit of training depending on what level you want to reach,” Preston said. “AI can leapfrog a lot of that training” because it’s easier to use.

Jacqueline Steubbel, 81, works to pay for basic living expenses and uses AI to boost her productivity.

Steubbel, who lives in Tennessee, worked as a copy editor for a newspaper while raising her four children. Two years ago, she secured a job as a psychiatric drug and alcohol addiction counselor, taking pride in helping many get back on track.

Steubbel said she’s watched videos about how to use ChatGPT and other tools at work. She employs it to search case histories for her patients and copyedit a nonfiction book she’s writing. She suspects AI will be crucial to advancing medicine in her field, but will never replace the human side of counseling.

“I’ve had a lot of good experiences,” Steubbel said. “It would be a shame not to leave some of that residue as I continue what I call my trek across the crackling Earth.”