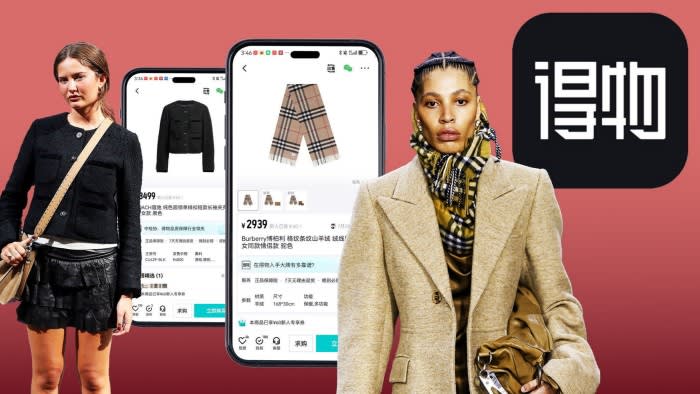

At a Burberry store in downtown Shanghai, the company’s distinctive tartan scarf costs Rmb4,800 ($678). But download the fashion app DeWu, upload a photo of the scarf and an identical-looking item pops up for just Rmb2,939.

In the same luxury mall, one of the most exclusive in China’s biggest city, a jacket from Coach is on sale for Rmb4,400 and a Prada hat for Rmb6,150. On DeWu, they respectively cost Rmb3,499 and Rmb4,939.

“I can’t guarantee you this one is for real,” said an assistant at one shop, looking at an image of designer garb on the app. “DeWu . . . how can I put this, of course it’s cheaper,” said another assistant.

DeWu, founded in 2015 by Jiangxi province-born billionaire Yang Bing as a platform to buy and resell sneakers, has become the beating heart of China’s vast luxury goods grey market, where goods bought outside the country are re-sold at cut-rate prices well below those in flagship stores.

“It’s the 800lb gorilla in the room,” said Jacques Rozien, managing director of Shanghai-based consultancy Digital Luxury Group. According to estimates, sales of top brands on DeWu now make up more than 70 per cent of what he calls a “thriving” grey market in China.

The grey market’s growth and increasing sophistication have huge implications for the global luxury industry, which has for the past decade relied heavily on mainland Chinese purchases to power growth but now faces a challenging economic backdrop.

Weaker consumer confidence has encouraged Chinese buyers to search for lower prices, while there are signs that falling luxury sales internationally are also encouraging more inventory to flow into the country through opaque grey market channels.

DeWu, which research group Hurun estimates was worth $10bn as of last year, allows anyone who sets up an account to sell merchandise, bypassing the brands themselves. The company, which has its own process to authenticate goods that Rozien says is trusted, is now so significant that it is used as a proxy for non-official sales of goods in mainland China.

DeWu, which is based in Shanghai, did not respond to a request for comment. Its app has been downloaded 350mn times in China, according to state media.

Re-Hub, a luxury intelligence company, has analysed public transactions on the site and estimates that sales across 48 brands on DeWu rose 19 per cent year on year in the second quarter to more than Rmb7bn.

“The implication is that grey market revenue [in China] is a bigger portion of brand revenue in 2024 than it was in 2023,” said Thomas Piachaud, head of strategy at Re-Hub, adding that this growth “outpaced or significantly outpaced the reported Q1 and Q2 growth rates globally and in China” for “the majority of brands”.

Most luxury brands do not work directly with the company, he said. But third parties can buy products overseas, especially through cheaper wholesale channels in Australia or South Korea, and then bring them into the mainland, where prices are typically higher, in part because of taxes.

There are a variety of potential routes, said Piachaud, from “a backdoor in the factory that some units go through and find their way into China” to a “direct relationship with [the] wholesale of the brand”.

Historically, these so-called daigou purchases were handled through small-scale WeChat groups. But there has been a “huge shift” towards “start ups” and “corporates”, said HSBC managing director Erwan Rambourg.

DeWu’s growth also points towards Chinese consumers’ heightened price sensitivity. This has combined with slowing global sales to hit luxury groups hard. Organic sales at Burberry and Kering, the group that owns Gucci and Saint Laurent, are down more than 20 per cent and 30 per cent, respectively, in the first half of the year, according to estimates from Barclays, putting pressure on retailers to deal with excess product.

“There is a lot of excess stock, a lot of discounting, and a lot of it is coming to China,” said one luxury industry executive in China. Much of it is coming from Hainan, a duty-free island in south China, the person said, and Japan because of the weak yen, as well as through traditional grey market routes such as Italy and the Middle East.

Top luxury brands such as Louis Vuitton, Hermes and Chanel carefully control their distribution networks and have little to no wholesale network, one of the main avenues through which products can leak into the grey market.

“Louis Vuitton products are exclusively sold in Louis Vuitton stores” and on official websites, the world’s biggest luxury brand said, adding that it never discounted products. “Discounted [items] on the web are invariably fake.”

During an earnings call last year, LVMH chief executive Bernard Arnault said his company was “fighting against so-called parallel exports”, a term for grey market channels.

“A number of our peers need to generate revenue and don’t hesitate to sell through resellers who buy products abroad and then sell them on at discounted prices in China, but we avoid that,” he said. “For your [brand] image, there is nothing worse. It’s dreadful.”

Kering is trying to reduce its wholesale retail globally. But for many others, it remains an important part of the business. For brands “with a large and somewhat uncontrolled wholesale channel”, sales on grey market platforms can account for 60-70 per cent or more of their total sales in mainland China, according to Bain.

In the mainland, DeWu is approaching brands directly to encourage them to open official stores on the platform, according to one person who operated such a relationship for an international group, though few have accepted.

On the app itself, items are shown at the lowest available price. Items that include original boxes fetch higher prices. Sellers are identified by a long serial number and the name of the city in which they are based.

Back in the Shanghai mall, there were almost no customers in any of the shops during one weekday afternoon before the National Day holiday. Meanwhile on DeWu, demand remained high for the Burberry scarf, with a long list of recent purchases.

“If it was going to happen anywhere, it was going to happen in China,” said Pichaud of the grey market’s rise. “People are always looking for the good deal, they’re looking for an easy solution.”

Additional reporting by Gloria Li in Hong Kong and Wang Xueqiao in Shanghai