This article is an on-site version of our Energy Source newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Tuesday and Thursday

One thing to start: The big news over the weekend in the US was the debt ceiling deal struck between the White House and Republicans. While it still needs to be approved by Congress, the deal delivers yet another win for West Virginia senator Joe Manchin, who managed to slip into the deal an expedited approval for the Mountain Valley Pipeline project.

Welcome back to Energy Source. The oil supermajors’ proxy season culminates with ExxonMobil’s and Chevron’s annual meetings tomorrow. Climate activists have already made a stir at the AGMs across the Atlantic, forcing fossil fuel bosses such as BP’s Bernard Looney and Shell’s Wael Sawan to defend their emissions plans. And Norway’s colossal sovereign wealth fund will side with climate activists against the boards of the US supermajors tomorrow.

Today we carry a candid op-ed from Mark van Baal, head of Follow This, a small activist shareholder which tabled some of the recent climate resolutions. Van Baal argues that institutional investors need to get serious about their own commitment to the Paris Agreement climate targets again. Exxon’s and Chevron’s responses to van Baal’s resolutions are in their proxy statements. Write in with your views: [email protected].

Meanwhile, voters in the oil-rich western Canadian province of Alberta, the US’s biggest source of foreign crude, went to the polls yesterday, electing Danielle Smith of the United Conservative Party as premier. For energy and climate watchers (or half-Albertans like me) the campaign was underwhelming. Even the brutal wildfires raging in the province during an abnormally dry spring didn’t spark serious discussion of climate change.

Will the result lead to more confrontation with Ottawa over climate policy and carbon taxes, or less? Either way, the province’s carbon-intensive oil sands are on the up again, as Myles reports.

Data Drill picks out some of the most startling takeaways from last week’s International Energy Agency report into global energy investment. Thanks for reading. — Derek

Opinion: Shareholders are crucial to unlocking energy transition

Mark van Baal is the founder of Follow This.

Every so often, the CEO of a big oil company invites me for coffee. I enjoy this courtesy, the swoosh of the lift, a seat at that big boardroom table — never mind the intention, I tell myself. Perhaps all this is a signal of respect.

Afterwards, I’m exhausted. Every time. The conversation goes like this: one of the executives will ask my organisation, Follow This, to withdraw our shareholder resolution from their company’s AGM. My colleagues and I reply that we’re seeking a shareholder mandate that will support management to lead the energy transition.

A short moment later, we shake hands — as if to confirm our disagreement. Then I make my way down the plush C-suite corridors back to the elevator.

Follow This is a movement of 9,000 shareholders in oil and gas companies. Our climate resolutions express support for oil majors — Shell, BP, TotalEnergies, Chevron, and ExxonMobil — to align their CO₂-emissions reduction targets with the Paris Agreement on climate change and invest accordingly.

Investors’ support for Follow This resolutions has grown from 2.7 per cent in 2016 to about one-third of AGM votes in 2021. This is a logical trajectory. Any investor contemplating the economic and environmental damage from carbon emissions needs to take a longer view of their fiduciary responsibility.

In 2022, the oil empire struck back. War in Ukraine triggered a surge in oil prices. Super profits for Big Oil and fears of growing energy insecurity lifted the defensive mood in those boardrooms. A sense of delayed vindication among oil industry executives was almost palpable when, last year, support for Follow This’s resolutions slumped.

Oil companies have claimed — defying logic or responsibility — that increasing investment in hydrocarbons is an imperative made more urgent by the energy crisis. A short-term panic in commodity markets eclipsed the larger catastrophe of climate crisis.

Of course, oil executives, experts in the intermittently lucrative business of turning hydrocarbons into petrodollars, are reluctant to lead the energy transition.

In the past year, we’ve met executives at 11 oil majors, every one determined to stick with what they know best — for as long as possible. Emboldened by their windfall profits, more than one has answered my entreaties with a simple question: how could he make the same profits from renewables?

That’s the wrong question. Time is up for Big Oil’s business model. Today’s profits should be funding exploration of new business models. My argument — that the business case for oil will collapse, just as soon as fossil fuel producers are held liable for climate damage — falls on deaf ears.

Today, investors know that the climate crisis poses a material risk to their entire portfolios. The consequences of floods, droughts and extreme weather have to be paid for. That’s why many institutions make public commitments of support for the Paris Agreement, which requires the world to almost halve emissions in this decade.

Others talk about constructive engagement and transition pathways, but to little effect. The right to vote at AGMs is the only meaningful power wielded by shareholders. Why then is it so difficult for the same institutions to vote in favour of resolutions that align with their announced policies to achieve the Paris goals?

I’ve heard many answers to that question. In 2016, when Follow This filed our first climate resolution at Shell, we were told that it was unusual to vote against the company’s board; unreasonable to ask for cuts in (so-called Scope 3) product emissions; and that it was unnecessary because oil companies had agreed to set Scope 3 targets — in the very distant future.

These excuses have worn thin. By 2022, the 10 largest investors in the Netherlands all voted in favour of our resolutions. In the UK, two of the four largest institutional investors (HSBC and Schroders) voted for the Follow This proposal last year.

The others, Abrdn and Legal General Investment Management, voted against. This allowed investors to “continue building on the constructive engagements” with oil companies, said LGIM. But as the Church of England pension fund has acknowledged, constructive engagement and voting for the Follow This resolution are not mutually exclusive. They’re codependent.

Asset managers, whose performance is measured quarterly, worry that setting medium-term Scope 3 emissions reduction targets would lead to a decline in short-term profits. In short, they prioritise short-term profits over long-term risk. This line of argument is a fallacy. Developing new oil and gas projects can take a decade or more. Investments made now to increase capacity herald climate disaster.

As long as investors allow Big Oil to do what they know best, oil and gas companies will stick to their strategy of investing more in new fossil fuels capacity far beyond the boundaries of the Paris Agreement, while lobbying against climate legislation, and even largely ignoring court rulings to curb all emissions in this decade.

Big Oil needs to change, or Paris will fail. That’s a decision for shareholders. (Mark van Baal)

Canada’s oil sands are back

Next week marks two years since the axing of the Keystone XL pipeline, which was set to pump heavy oil from Alberta to refineries on the US Gulf Coast. The implosion of the project, many commentators said at the time, was another nail in the coffin of the Canadian oil sands.

But now things are looking up for Alberta’s oil sands, the world’s third-largest deposit of crude — and one of its dirtiest.

The oil sands are set to produce 3.7mn barrels of oil a day by the end of the decade, according to a new outlook from S&P Global Commodity Insights. That is half a million barrels a day more than today — and 140,000 b/d more than forecast a year ago.

The revision might be modest, but it marks the first time S&P, an authority on global output, has upped its production forecast in five years. And it suggests that the death of the oil sands has been exaggerated.

“Many people prophesied about writing its epitaph,” Kevin Birn, vice-president and Canadian oil markets chief analyst at S&P Global Commodity Insights, told ES.

But while raising capital for big new projects had become challenging, he said, the sector had become increasingly adept at extracting ever greater volumes from existing projects, while still returning large amounts of cash to shareholders.

“What we’re really seeing is this large installed capacity that was built out over many years and the industry trying to squeeze that capacity to maximise output.”

Canada is the world’s fourth-biggest oil producer, pumping 4.8mn b/d of oil last year, of which oil sands accounted for 3.2mn b/d.

The increase in production to 2030 underlines the staying power of the sector in a world increasingly focused — rhetorically at least — on cutting emissions. While the foreign oil majors have mostly pulled out of oil sands, local producers are juicing more oil out of projects by making small tweaks. Unlike shale, where production declines rapidly, oil sands project can hold production relatively stable for years.

Still, oil sands production — with its significant ecological impact and high emissions profile — remains in the crosshairs of environmentalists. The difficulties of extracting and upgrading bitumen from the oil sands makes them one of the most carbon-intensive sources of oil on the planet. The sector is also one of the fastest-growing sources of greenhouse gas pollution in Canada, with total emissions up by a factor of 10 over the past 30 years.

And as authorities in Ottawa look to square net zero goals with continued production, the federal government is pushing forward with an oil and gas cap which is set to establish an absolute emissions level for the oil sands. That is already taking its toll.

“Although we are seeing growth, that has kind of sterilised investment a little bit,” Celina Hwang, director of North American crude oil markets at S&P, told ES.

“At these prices I think the marketer might anticipate more growth . . . But we’re not really seeing the same level that we might have.” (Myles McCormick)

Data Drill

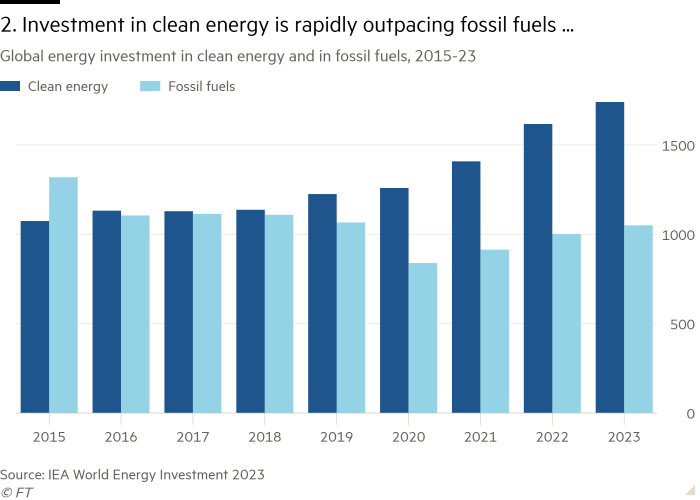

The International Energy Agency released its annual World Energy Investment report last week.

It contained plenty of data to crunch. Here are three things that we found particularly interesting.

Power Points

Energy Source is written and edited by Derek Brower, Myles McCormick, Justin Jacobs, Amanda Chu and Emily Goldberg. Reach us at [email protected] and follow us on Twitter at @FTEnergy. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Moral Money — Our unmissable newsletter on socially responsible business, sustainable finance and more. Sign up here

The Climate Graphic: Explained — Understanding the most important climate data of the week. Sign up here