The rich have always been welcomed in Switzerland. To spend, but more importantly to hoard. Across the country, in secretive locations, banks operate underground vaults and storage facilities — often converted military bunkers that have been hewn from mountain rock. Some have no roads nearby and can only be accessed by air.

At one facility 40km south of Lucerne, storage company Brünig Mega Safe is carving into an imposing mountain and plans to offer “professional and secure storage of assets in underground caverns” for anything from gold bars and stock certificates to artworks and classic cars. Prices start at $500,000 for a 25 sqm vault.

For three centuries, the country has also offered the rich reliable, specialist advice on managing and investing their money. In times of war, political turmoil and rising taxes, the country’s stability and geopolitical neutrality — combined with its strict adherence to banking discretion — supported a thriving and world-leading wealth management industry.

But, in recent years, those foundations have begun to crack — and its rivals in Asia are looking on. Under international pressure, Switzerland has been chipping away at its banking secrecy laws that restrict banks from passing on details about their clients to governments. And the country’s decision to sanction Russian oligarchs following Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine nearly three years ago has dented its reputation for international neutrality.

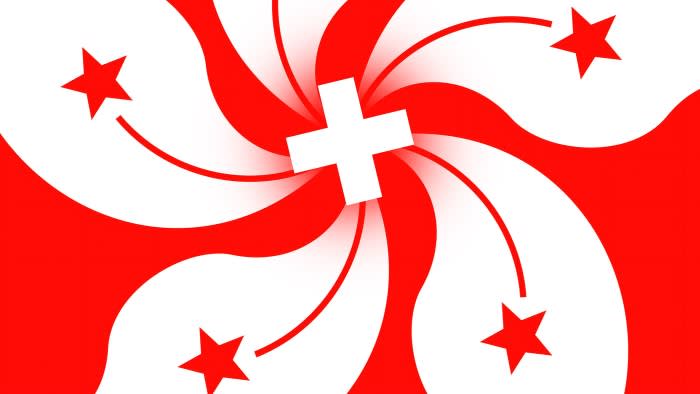

Meanwhile, the collapse last year of Credit Suisse — the country’s second-biggest bank, trusted by millions of wealthy clients globally — has cast a shadow over Switzerland’s claim to be a stable nation with a sturdy financial services sector. The remainder of the Swiss banking sector is aware of what this means. “Singapore and Hong Kong are going to be more and more important competitors to Switzerland as global hubs,” says Giorgio Pradelli, chief executive of Swiss private bank EFG, which operates in all three countries and is increasingly focused on Asia.

In fact, Hong Kong is set to overtake Switzerland as the world’s biggest offshore wealth hub by 2028, with Singapore not far behind. Hong Kong would then account for $3.2tn out of the total $17.1tn in global offshore wealth assets, compared with $3.1tn for Switzerland and $2.5tn for Singapore, according to Boston Consulting Group estimates.

In the five years to 2028, Hong Kong’s cross-border wealth market is on track to grow by 6 per cent a year in terms of assets, compared with 3.6 per cent in Switzerland and 8.5 per cent in Singapore.

“Switzerland will always be our competitor, but we are not afraid,” says Jason Fong, a 27-year banking and asset management veteran who has been tasked by the Hong Kong government with attracting family offices to the Chinese territory. “They are crumbling and we are in a very advantageous situation.”

Much has changed since the early 18th century, when France’s Catholic kings tapped the banks of Geneva for funds, but tried to conceal their dealings with the city’s Huguenot financiers, fearing a sectarian backlash at home. An edict from the Great Council of Geneva in 1713 prohibited bankers from sharing client registers with the authorities.

Geneva’s commitment to banking discretion helped elevate it into a European financial powerhouse and drew in Swiss mercenary soldiers who were looking to safeguard their money made from fighting abroad. “The Swiss laid the foundation for today’s global wealth management model,” says Iqbal Khan, co-head of wealth management at UBS. “Its heritage comes from the duty of care for others’ property and the principle of self-control.”

Secrecy became enshrined in Swiss legislation with a 1934 banking law, which set out that bankers who disclosed client information could be jailed. Initially, European Jews fleeing persecution set up Swiss bank accounts to protect their valuables, but later such accounts were favoured by Nazis to store their looted wealth. A Swiss bank account soon became the financial product of choice for the rich who did not want too much attention on their fortunes’ sources.

This commitment to clandestine banking attracted despots and oligarchs throughout the 20th century, while tax-evading lawyers and country doctors from neighbouring European countries made up a large proportion of Swiss private banks’ clients. It was in the middle of the 20th century that Swiss bankers attracted the nickname of the “gnomes of Zurich” from British politicians for their ability to hoard heaps of gold in underground vaults. It was soon regarded as a badge of honour. Swiss bankers took to answering calls from British colleagues by saying: “Hello, gnome speaking.”

More recently, though, under pressure from tax authorities around the world following a series of high-profile scandals over the flows of illicit money, Switzerland has acquiesced to demands for greater transparency around its banking sector.

In 2017, it signed up to the international automatic exchange of information standard, which requires Swiss financial institutions to share details on their clients with the countries where they are tax resident. More than 100 countries are signed up to the same standard, which has all but killed off Switzerland’s allure for tax evaders.

The final blow for Swiss banking discretion came two years ago with the Suisse Secrets scandal, where documents detailing the accounts of 30,000 Credit Suisse clients were leaked to a consortium of international media outlets. Among those named in the cache of documents — which dated back to the 1940s — were war criminals, autocrats, oligarchs, drug smugglers and human traffickers.

The collapse of Credit Suisse prompted the Swiss government to devise a series of proposals to bolster the banking system, including giving more power to the domestic financial regulator and potentially increasing UBS’s capital requirements. Executives in Zurich fear that if the new measures are too draconian, they could ultimately put their banks at a disadvantage to their foreign rivals.

“Financial centres like Hong Kong, Singapore and the US are aggressively competing, and making great progress, for the offshore wealth management crown that Switzerland holds today,” UBS chief executive Sergio Ermotti said in June. “Foreign financial centres would benefit if Switzerland were to restrict its ability to maintain a leading presence abroad.”

Switzerland’s reputation for neutrality on the world stage has proved enticing over the decades for the global and mobile rich, especially in times of rising geopolitical tension. Yet this, too, is being tested. The decision by Switzerland following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to sign up to the US and EU sanctions regimes has led to questions from clients about whether the country is still an impartial player.

A recent report from the Swiss Bankers Association lobby group identified Switzerland’s adherence to international sanctions regimes as the top geopolitical risk facing the country’s wealth managers. The immediate effect of implementing sanctions was Swiss banks pulling out of Russia and jettisoning Russian clients, many of whom switched their offshore bank accounts to the Middle East.

Jimmy Lee, head of Asia-Pacific at Julius Baer, has run several western banks’ Singapore and Hong Kong operations over the past three decades. He says he is often asked by clients whether Switzerland is still neutral. “We explain to them that Ukraine is at the doorstep of Switzerland and they are taking a stance,” he says. “If your neighbour’s house is on fire, you cannot stay neutral.”

The Ukraine war has brought Switzerland closer to Nato, with a recent paper commissioned by the country’s defence ministry suggesting Swiss troops could co-operate in military manoeuvres with other states for the first time since 1515.

As Switzerland grapples with its five-century-old commitment to neutrality, rival wealth management hubs have sought to project their own credentials as non-partisan places to do business. “Some of these Asian wealth hubs played their hand extremely well,” says a Swiss bank executive. “They managed to position themselves as neutral, although they all adopted the US sanctions just like we did.”

The story of how Asia’s two main financial entrepôts copied the Swiss white-glove model of wealth management and ended up outpacing their European rival could be seen as a historical quirk — a byproduct of the supercharged growth in Asian wealth in the 21st century. But, in Singapore’s case, it was more by design. It was on a trip to Zurich in 1967, two years after Singapore’s independence from Malaysia, that Lee Kuan Yew set upon the idea of transforming the nation he had founded into Asia’s financial hub. Lee, the country’s first prime minister, had seen the way Switzerland, a small country with few natural resources and surrounded by powerful neighbours, had established itself over several centuries as the global centre of offshore banking and wealth management.

Singapore’s government followed Switzerland’s lead in designing its tax system to attract rich foreigners looking for a base to park their wealth, while also encouraging Swiss private banks to set up shop. “We have . . . deliberately encouraged the development of Singapore as a financial centre,” Lee said on a subsequent trip to Zurich in 1971 while speaking at a reception at the Union Bank of Switzerland. “Singapore sets out to be to south-east Asia what Switzerland is to Europe — a money and gold market.”

Part of the reason for the rise of Hong Kong and Singapore as offshore wealth hubs is down to demographics and how quickly a wealthy upper class has emerged in Asia in recent decades. Mainland China is now home to 6mn millionaires, the second-highest number behind the US. This weight of money funnelling into Hong Kong from mainland China, which accounts for just under half of the cross-border money flowing into Hong Kong’s wealth managers, according to McKinsey, has driven its rapid growth — even as that of Switzerland and Singapore, to a lesser extent, has slowed.

This proximity is one of the main reasons UBS recently announced it would move its local headquarters to a tower sitting on top of the West Kowloon train terminus. The new development is designed to connect Hong Kong by high-speed rail to the surrounding Greater Bay Area, the largest and most populated urban area in the world.

By contrast, Singapore acts more like an entry point for global investors into south-east, and increasingly, north Asia. China is expected to account for about 30 per cent of wealth inflows into the city state over the next five years, with Hong Kong and Taiwan the next biggest markets.

A sign of Hong Kong and Singapore’s growing importance as offshore wealth hubs is the booming market for family offices. These small, private companies are set up to manage the wealth of one or maybe a handful of wealthy families, providing a full suite of services, from tax and succession planning to investing and philanthropy. Both Hong Kong and Singapore are on course to report record numbers of launches this year. There were 50 family offices operating in Singapore in 2018, but that has ballooned to 1,650 today. Hong Kong, meanwhile, has more than 2,700.

The new launches are typically serving families in other Asian countries looking to diversify where their wealth is managed, transferring a large chunk from their domestic market to meet their global interests or give them options if things get uncomfortable at home. Singapore, in particular, is attracting family office branches from further afield. “Some are coming from the Middle East and Europe,” says Jin Yee Young, co-head of Asia-Pacific wealth management at UBS, who runs the Singapore business. “They see Singapore as a window to the region. They are very established, some are even multigenerational family offices, and they are looking to tap into investments in the region.”

When Hong Kong and Singapore were starting to establish their wealth management sectors, they looked to the Swiss model for inspiration. Yet for a long time, the clients had vastly different needs. “When I started in private banking in the 1990s, it was about the private individual and their needs,” says Amy Yo, the other co-head of UBS’s Apac wealth business, who runs the Hong Kong operation. “As things have globalised, 70 per cent of our clients are entrepreneurs and now it is much more about succession planning, looking after their businesses, philanthropy and doing good for society.”

The authorities in Singapore and Hong Kong are working on ways to improve the local talent pools to ensure they can meet evolving client needs. “Whenever I go to the Asian international financial centres, the general discussion is always on how to increase the number of people who are interested in working in wealth management,” says Pradelli of EFG. “Talent is very important. While we traditionally have a strong talent base for our industry in Switzerland, the pipeline of talent in Asian financial centres is strong and improving, but still quite scarce.”

Singapore has had an influx of money from China and Hong Kong in recent years, as rich individuals moved their wealth from what they regard as an increasingly authoritarian Chinese state. But those inflows culminated in a S$3bn ($2.34bn) scandal last year, in which 10 Chinese nationals were convicted of money laundering following Singapore’s biggest investigation into online gambling in Asia. It involved island-wide raids and the seizure of gold bars, expensive wines, crypto assets, designer handbags and luxury cars. Banks in Singapore have responded by heightening scrutiny of foreign customers and intensifying efforts to identify sources of wealth, leading to delays in onboarding new customers.

While some critics have suggested the episode highlighted lax controls in Singapore’s burgeoning family office sector, Marco Pagliara, head of emerging markets at Deutsche Bank’s private bank, attributes it more to growing pains that the local regulator responded to.

“There was a phase where there was a significant flow coming from north Asia — on the back of that there was correction that needed to be implemented. They did it quite swiftly,” says Pagliara. “Singapore is focused on running a very tight and organised ship with the way they manage their financial centre.”

This month, the Singaporean government published a package of recommendations to tighten anti-money-laundering rules in the city state, including improving information sharing between departments and giving prosecutors stronger powers. “We continually engage the industry and stakeholders to ensure that our framework remains robust against illegitimate wealth and welcoming of legitimate businesses and investors,” said the Monetary Authority of Singapore, the country’s financial regulator.

Though their home market has been losing ground, Switzerland’s wealth managers are seeking to capitalise on the growth in Asia by building on the cachet associated with being a Swiss bank. “Swissness stands for high quality, trust and credibility,” says UBS’s Khan, who recently relocated to Hong Kong to run the bank’s Asia-Pacific business. “But that’s not enough in today’s world. You need to have cultural heritage as well.”

Khan, who will split his time between Hong Kong and Singapore, had previously been the sole head of UBS’s wealth management business and was based in Zurich. But he is one of several senior executives at European wealth managers who have relocated to Asia as they target the region for growth. Asia’s biggest banks were mostly late to prioritise developing their own wealth management businesses and trail far behind their longer established competitors from Europe and the US. But they are starting to catch up.

The Swiss banks have recognised that although their country’s reputation as the world’s centre for wealth management has taken a hit in recent years, they can still dominate in rival financial hubs.

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment