Don’t let the soft, sepia tones fool you — the United States used to be dangerously polluted.

Before President Richard Nixon created the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, the environment and its well-being was not a federal priority.

Federal actions like the 1970 Clean Air Act and the 1972 Clean Water Act helped regulate water and air pollution, changing the landscape of American cities.

Since President Donald Trump returned to office in January, his administration and EPA administrator Lee Zeldin have sought to roll back environmental protections aimed at tackling widespread pollution.

Among its efforts, the EPA’s scientific research arm, the Office of Research and Development, is being dismantled, leaving thousands of workers without jobs, the agency announced earlier this month. The agency said it will create a new Office of Applied Science and Environmental Solutions, which it said will focus on research and ultimately save the EPA nearly $750 million.

Zeldin said in a statement that the changes mean the EPA “is better equipped than ever to deliver on our core mission of protecting human health and the environment, while Powering the Great American Comeback.”

The actions fall in line with the administration’s wider goal of promoting government efficiency across federal agencies, while pursuing policies that boost US production and the use of fossil fuels.

“The obliteration of ORD will have generational impacts on Americans’ health and safety,” said Rep. Zoe Lofgren of California, who is on the House Science Committee, the AP reported.

In the early 1970s, the EPA launched the “The Documerica Project,” which leveraged 100 freelance photographers to document what the US looked like. By 1974, they had taken 81,000 photos. The National Archives digitized nearly 16,000 and made them available online.

We’ve selected 36 of the photos to reflect on how cities across the US used to look.

In the San Francisco Bay, raw sewage entered the bay in 83 places.

Belinda Rain/EPA

By the 1970s, the San Francisco Bay was badly polluted, with sewage and wastewater from industrial facilities dumping in the bay from over 83 points of entry, the San Francisco Baykeeper reported.

Pollutants in the sewage dumped in the Bay peaked in the late 1960s, according to the California State Water Resources Control Board.

The Environmental Protection Agency started regulating emissions, waste, and water pollutants after it was established in 1970.

In San Francisco Bay, the Leslie salt ponds gleam at sunset. The photographer behind this photo said the “water stinks.”

Belinda Rain / EPA

In 2019, the EPA ruled the land, owned by Cargill Salt, was not bound by the Clean Water Act, Mercury News reported.

Today, battles remain over who can be held responsible for the water quality off the coast of San Francisco — a Supreme Court ruling earlier this year could impact the EPA’s power to enforce water quality regulations.

The court sided with the city of San Francisco in a 5-4 decision, arguing the agency didn’t have the power to enforce broad regulations on the quality of a body of water. While the agency can instruct permitholders to follow certain requirements in a bid to avoid pollution, it shouldn’t hold them responsible for the ultimate quality of the water, which is out of their control, the court said.

Industrial black smoke billows out of a stack in San Francisco.

Belinda Rain / EPA

During the 1970s, the biggest problem for the city was ozone pollution, which mainly comes from cars, industrial plants, power plants, and refineries.

The Clean Air Act, passed in 1970, allowed the EPA to set regulations for industrial pollution and authorized the agency to create National Ambient Air Quality Standards to promote air quality regulation throughout the country.

Here is one of the factories that polluted San Francisco.

Belinda Rain / EPA

The photo was taken in 1972, according to the National Archives.

In Baltimore, trash and tires cover the shore at Middle Branch beside the harbor in 1973.

Jim Pickerell/EPA

The EPA regulates waste now, and sets criteria for landfills. While the open dumping of waste is banned, it still happens.

Baltimore City did have some simple techniques to keep the harbor clean.

Jim Pickerell/EPA

Here, a screen has been placed across the water to trap trash. A heavy rain could break it, but it was effective when cleaned often.

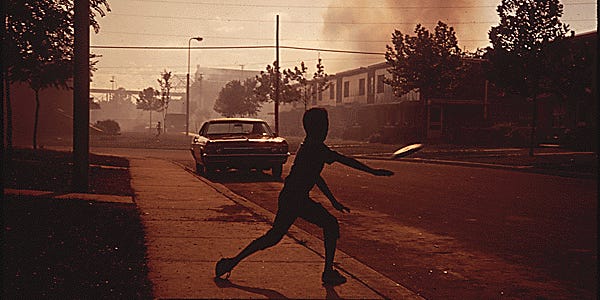

In Birmingham in 1972, a boy throws a Frisbee against hazy skies.

LeRoy Woodson/EPA

Truckers in the 1960s called Birmingham “smoke city,” Bham Now reported.

A house in North Birmingham is barely visible in industrial smog coming from the North Birmingham Pipe Plant.

LeRoy Woodson/EPA

North Birmingham was the most polluted area of the city.

In Cleveland, in 1973, billowing smoke casts a gloom over the Clark Avenue bridge.

Frank Aleksandrowicz/EPA

Because Cleveland was an industrial city, the pollution was severe.

Cleveland’s inner city was also a dumping ground.

Frank Aleksandrowicz/EPA

In this photo from 1973, an empty lot on Superior Avenue, Cleveland, was filled with trash.

In Delaware, the city incinerator billows out smoke over the river.

Dick Swanson/EPA

In 2016, a report released by New York University said 41 people living in Delaware still die because of air pollution every year, The News Journal reported.

In Denver, murky light brown sewage is discharged into the South Platte River.

Bruce McAllister/EPA

The sewage came from the Metro Sewage Treatment Plant, per the EPA.

Here’s a billboard against Denver’s smoky skies in the 1970s. The city was known for having a brown cloud of pollution.

Bill Gillette/EPA

In the late 1980s, the air pollution got so bad, the city developed a visibility standard — it asked whether downtown workers could see mountains that were only 35 miles away, The New York Times reported.

In Kansas City’s harbor, on the Missouri River, a local EPA worker points out a dying fish.

Kenneth Paik/EPA

While the river has been much cleaner since the Clean Water Act was passed, trash and industrial contaminants still end up in it, The Kansas City Star reported. In 2023, NPR reported that volunteers with Missouri River Relief have picked up more than 2 million pounds of trash from the river since the organization began in 2001.

In Los Angeles, the outline of the sun can be clearly seen because air pollution creates a buffer.

Charles O’Rear/Documerica

In 1943, 30 years before this photo was taken, the smog was so bad, the city’s residents thought there was a gas attack, according to the California Sun.

Los Angeles county monitored pollution on the roads, at least.

Gene Daniels / EPA

In this photo from 1972, the air-pollution control department checks for violators.

In New Orleans, fumes spread over the streets.

John Messina / EPA

Fumes billow from Kaiser Aluminum Plant’s smoke stack in 1973.

In an illegal dump in New Orleans, garbage turned to sludge when a lake overflowed into it.

John Messina / EPA

In the 1970s, the EPA found 66 pollutants in the city’s drinking water. And the city’s water is known for its oily taste, per The Washington Post.

In New Jersey, a photo shows raw and partially digested sewage.

Alexander Hope / EPA

The sewage was photographed darkening the water in Bayonne, New Jersey, in 1974.

New York is one of the most photographed cities for “The Documerica Project.”

Gary Miller / EPA

Here, a pile of illegally dumped trash ruins the view of Manhattan and the Twin Towers in 1973.

A photographer snapped this image of an abandoned, waterlogged car in Jamaica Bay, New York.

Arthur Tress/Documerica The

The abandoned Beetle was photographed in 1973.

Another car has sunk halfway into the beach at Breezy Point, south of Jamaica Bay.

Arthur Tress / Documerica

The EPA now helps regulate how the city disposes of trash to prevent dumping in the Atlantic.

Though it might not be clear, this is the George Washington Bridge going over the Hudson River, covered in thick smog.

Chester Higgins / EPA

In 1965, a study by New York City Council found breathing New York’s air had the same effect as smoking two packets of cigarettes a day, The New York Times reported.

Seen here is the Statue of Liberty surrounded by oil. It was the result of one of 300 oil spills in the first six months of 1973.

Chester Higgins / Documerica

Between April and June of that year, 487,000 gallons of oil were dispersed in the New York Harbor and its tributaries, The New York Times reported.

The EPA estimated about 6 million gallons of coal were dumped into the New York Bight by the Edison Power Plant in Manhattan in the early 1970s.

Alexander Hope / EPA

The New York Bight is a triangular area that reaches from Cape May in New Jersey to the eastern tip of Long Island. The city allowed a ConEd plant to burn coal in the 1970s amid a fuel shortage, The New York Times reported. But coal has caused air and water pollution and destroyed wetlands, according to the National Archives.

Barges, filled with New York’s waste, are pulled down the East River to a Staten Island landfill.

Gary Miller / EPA

In the 1970s, New York produced 26,000 tons of solid waste every day, according to the National Archives.

Rubble is loaded into barges before being dumped offshore, on a debris dump site, in the New York Bight.

Alexander Hope / EPA

There were different distances for dumping different substances.

This is one of four New York City-owned vessels on its way to dump sludge 12 miles into the bight. In 1973, 5.8 million cubic yards of sludge was dumped, according to the National Archives.

Alexander Hope / EPA

The sludge would settle on the bottom of the ocean, “like mud, killing plant life and creating what has been described as a “‘dead sea,'” The New York Times reported.

Acid waste lightens the water here. It was also dumped in the New York Bight, 15 miles offshore, and made up 90% of industrial waste dumped in the area.

Alexander Hope / EPA

In 1974, more than 3 million tons were dumped in the bight, according to the National Archives.

Some roads in Manhattan, like 108th Street and Lexington Avenue, were covered with piles of trash.

Gary Miller / EPA

A photo shows trash strewn across New York City streets in 1973.

But it was worse in the Bronx. Here, the Bronx’s Co-Op City housing development is beside a landfill that was still being used, even though it had exceeded its dumping capacity.

Gary Miller / EPA

By 1992, regulations to prevent waste from being dumped on the shores around the city and efforts to clean them up had begun, with The New York Times reporting the end of the era of “using the ocean as a municipal chamber pot.”

In Philadelphia, the sun is setting, but because of the smog it’s hard to tell.

Dick Swanson / EPA

In 2018, a study found the city was becoming more polluted between 2014 and 2016, after several years of decreasing pollution, Philadelphia magazine reported.

In Pittsburgh, thick smoke creates a haze over the city.

John Alexandrowicz / EPA

The city was once dubbed “Hell with the lid off,” per The Allegheny Front.

A junkyard looms in front of the Monongahela River, which runs through Pittsburgh.

John Alexandrowicz / EPA

According to Mayor Tom Murphy in 2001, the biggest complaint he heard about the city was that it was too dirty, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported.

Near Pittsburgh, oil-coated trees on the shore of the Ohio River show the damage done by spills and industry.

John Alexandrowicz / EPA

NPR reported that the river is much cleaner today, 50 years since the Clean Water Act.

In Washington DC, raw sewage flows out into the Potomac river. In 1970, a hot summer resulted in a “stomach-turning” smell coming from the Potomac, due to the mixing of sewage and algae.

John Neubauer / EPA

The pollution was blamed on a “hundred years of under-estimates, bad decisions, and outright mistakes,” a director of the Federal Water Quality Administration told The New York Times.

His description can be applied to a lot of the US before the EPA.

This story was originally published in August 2019 and was most recently updated in July 2025.