President Trump has signaled that he will announce further tariffs this week on semiconductors as he moves forward with a trade investigation related to national security.

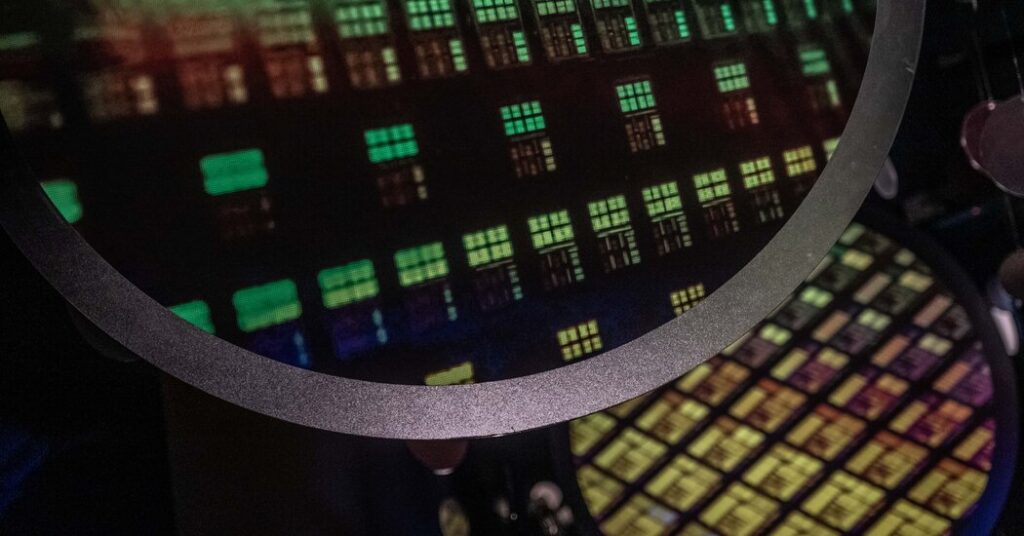

The move would raise the cost of importing chips, which are a vital component in electronics, cars, toys and other goods. The United States is heavily dependent on semiconductors from Taiwan and elsewhere in Asia, a reliance that Democrats and Republicans alike have described as a major national security risk.

Mr. Trump has argued that the tariffs would encourage companies to produce more chips domestically, though some critics have questioned how effective tariffs would be at relocating an industry largely centered in Asia.

Speaking Sunday night from Air Force One, the president said tariffs on electronics would “be announced very soon,” but suggested there might be room for exemptions.

“I’m a very flexible person. I don’t change my mind, but I’m flexible,” Mr. Trump said on Monday, when asked about those possible exemptions. He added that he had spoken to Apple’s chief executive, Tim Cook, and “helped” him recently.

The measures would come after Mr. Trump abruptly changed course on taxing electronic imports in recent days.

Amid a spat with China, Mr. Trump last week raised tariffs on Chinese imports to an eye-watering minimum of 145 percent, before exempting smartphones, laptops, TVs and other electronics on Friday. Those goods make up about a quarter of U.S. imports from China.

The administration argued that the move was simply a “clarification,” saying those electronics would be included within the scope of the national security investigation on chips.

But industry executives and analysts have questioned whether the administration’s real motivation might have been to avoid a backlash tied to a sharp increase in prices for many consumer electronics — or to help tech companies like Apple that have reached out to the White House in recent days to argue that the tariffs would harm them.

“The higher the tariff, the faster they come,” the president told reporters in the Oval Office on Monday, when asked about his timing and approach to issuing new tariffs on semiconductors as well as pharmaceuticals, another industry he has sought to attract to the United States.

“We don’t make our own drugs anymore,” Mr. Trump said.

Mr. Trump has abruptly raised and lowered many tariff rates over the past week, roiling financial markets and changing the stakes for companies globally. The president announced a program of global, “reciprocal” tariffs on April 2, including high levies on countries that make many electronics, like Vietnam. But after turmoil in the bond market, he paused those global tariffs for 90 days so his government could carry out trade negotiations with other countries.

Those import taxes came in addition to other tariffs Mr. Trump has put on a variety of sectors and countries, including a 10 percent tariff on all U.S. imports, a 25 percent tariff on steel, aluminum and cars, and a 25 percent tariff on many goods from Canada and Mexico. Altogether, the moves have increased U.S. tariffs to levels not seen in over a century.

The semiconductor tariffs would be issued under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which allows the president to impose tariffs to protect U.S. national security. The president has already used that legal authority to issue tariffs on imported steel, aluminum and automobiles. The administration is also using the authority to carry out investigations into imports of lumber and copper, and is expected to begin an inquiry into pharmaceuticals soon.

Kevin Hassett, the director of the White House National Economic Council, told reporters on Monday that the chip tariffs were needed for national security.

“The example I like to use is, if you have a cannon, but you’re getting the cannonballs from an adversary, then if there were to be some kind of action, then you might run out of cannonballs,” he said. “And so you can put a tariff on the cannonballs.”

Mr. Trump has argued that tariffs on chips will force companies to relocate their factories to the United States. But some critics have questioned how much tariffs will really help to bolster the U.S. industry, given that the Trump administration is also threatening to pull back on grants given to chip factories by the Biden administration. And foreign governments like China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan all subsidize semiconductor manufacturing heavily with tools like grants and tax breaks.

Globally, 105 new chip factories, or fabs, are set to come online through 2028, according to data compiled by SEMI, an association of global semiconductor suppliers. Fifteen of those are planned for the United States, while the bulk are in Asia.

Mr. Trump has criticized the CHIPS Act, a $50 billion program established under the Biden administration and aimed at offering incentives for chip manufacturing in the United States. He has called the grants a waste of money and insisted that tariffs alone are enough to encourage domestic chip production.

Jimmy Goodrich, a senior adviser to the RAND Corporation for technology analysis, said tariffs could be effective “if used smartly, as part of a broader strategy to revitalize American chip making that includes domestic manufacturing and chip purchase preferential tax credits, along with clever ways to limit the coming tsunami of Chinese chip oversupply.”

“However, the United States on its own only accounts for about a quarter of all global demand for goods with chips in them, so working with allied nations is critical,” he added.

Administration officials have suggested that chip tariffs could be applied to semiconductors that come into the United States within other devices. Most chips are not directly imported — rather, they are assembled into electronics, toys and auto parts in Asia or Mexico before being shipped into the United States.

The United States has no system to apply tariffs to chips encased within other products, but the Office of the United States Trade Representative began looking into this question during the Biden administration. Chip industry executives say such a system would be difficult to establish, but possible.

Some tech companies have been responsive to the president’s requests to build more in the United States. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, the world’s largest chip manufacturer, announced at the White House in March that it would spend $100 billion in the United States over the next four years to expand its production capacity.

Apple has also announced that it will spend $500 billion in the United States over the next four years to expand facilities around the country.

On Monday, Nvidia, the chipmaker, announced that it would produce supercomputers for artificial intelligence made entirely in the United States. In the next four years, the company said, it will produce up to $500 billion of A.I. infrastructure in the United States in partnership with TSMC and other companies.

“The engines of the world’s A.I. infrastructure are being built in the United States for the first time,” Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s chief executive, said in a statement.

The White House blasted out the news in an announcement that credited the president.

“It’s the Trump Effect in action,” the statement said. “Onshoring these industries is good for the American worker, good for the American economy and good for American national security — and the best is yet to come.”

Tripp Mickle contributed reporting.